By Audrey Wang, AGGV Volunteer

The title of the exhibition “Unformable Things: Emily Carr and Some Canadian Modernists” does not serve to place Victoria’s favourite artist on a pedestal while dismissing the other modernist artists of the time. Instead, the title hints at the limitations faced by Chief Curator Michelle Jacques when putting together the show. The AGGV collection is rich in its holdings of Emily Carr works, but more limited in some of the other equally important proponents of this movement in Canada. The curating of the exhibition, however, appears to represent the opposite. Emily Carr’s works are hung throughout the gallery space to compare and contrast with the works of David Milne, Lawren Harris, A.Y. Jackson, Vera Weatherbie and many others, giving the viewer a chance to come to terms with the meanings behind the paintings and the artists’ take on exploring the varied landscapes of Canada.

The 1920s was a lively era in Canada for artists who were seeking to break free from past conventions and to move towards more experimental approaches to painting. What we now term as the Modernist period saw artists rejecting representation and similitude in art, in favour of “the unformable things one wants to paint”, as Carr so expressed.

In Canada, modernism was focussed on landscape painting, rather than depicting the urbanization of the modern world which was the preferred subject-matter in Europe. This is in part due to the Group of Seven whose prominence created an art movement unique to Canada. The sweeping rugged landscapes, however, have prompted critics to argue that the paintings gave the impression of pristine, uninhabited landscapes, when in fact the areas depicted have been lived in for several millennia. With this narrative in mind, during her Curator’s tour, Jacques points out the difference between Emily Carr’s Big Eagle, Skidigate, B.C. (1929) painting and Anne Savage’s painting Skeena. B.C. (1928) of indistinct totems in the distance. The viewpoints in each work suggest different relationships with First Nations relics. In one, the totems are depicted as a compositional aspect of the natural landscape and in the other, the towering structure offers an expression of reverence.

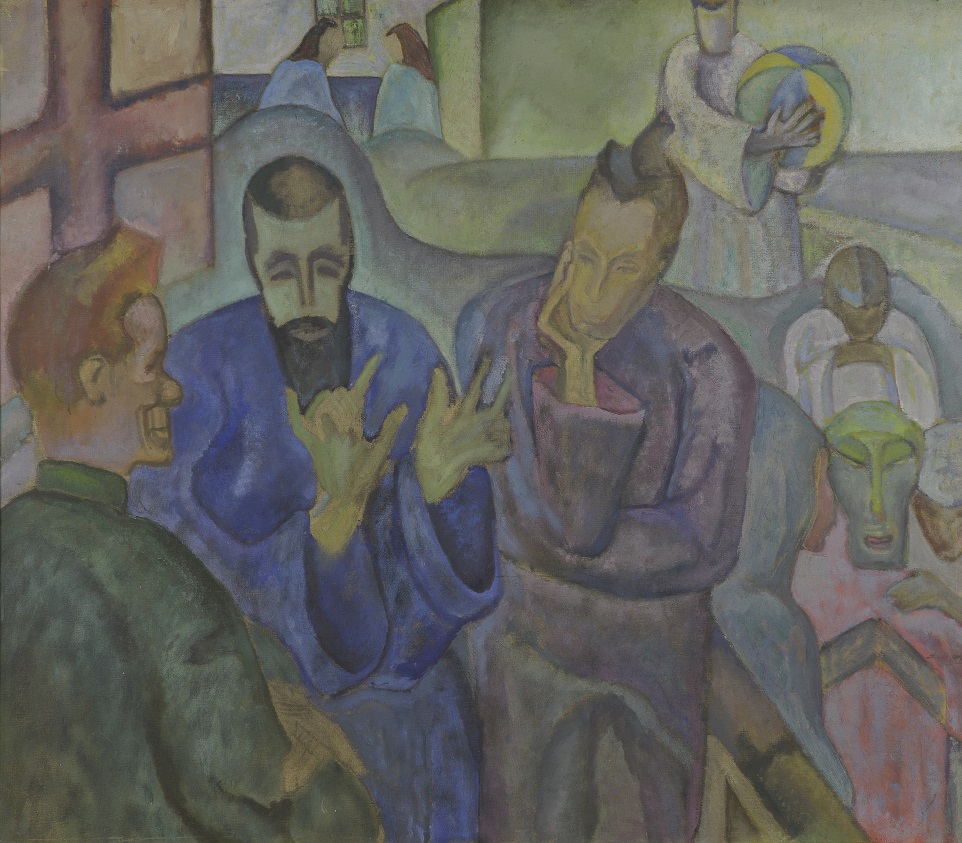

Carr’s Big Eagle, Skidigate, B.C. is also juxtaposed with Vera Weatherbie’s intriguing group portrait, Varley, Tauber, Macdonald (c. 1934). In both paintings, the artists have called upon cross-cultural elements for their subject-matter. In Carr’s painting, it is the Indigenous totem and in Weatherbie’s work, the viewer’s eye is quickly drawn to the fourth face in the painting, an African mask. This brings up the sometimes uncomfortable discussion of cultural appropriation and the effects of colonialism on other cultures.

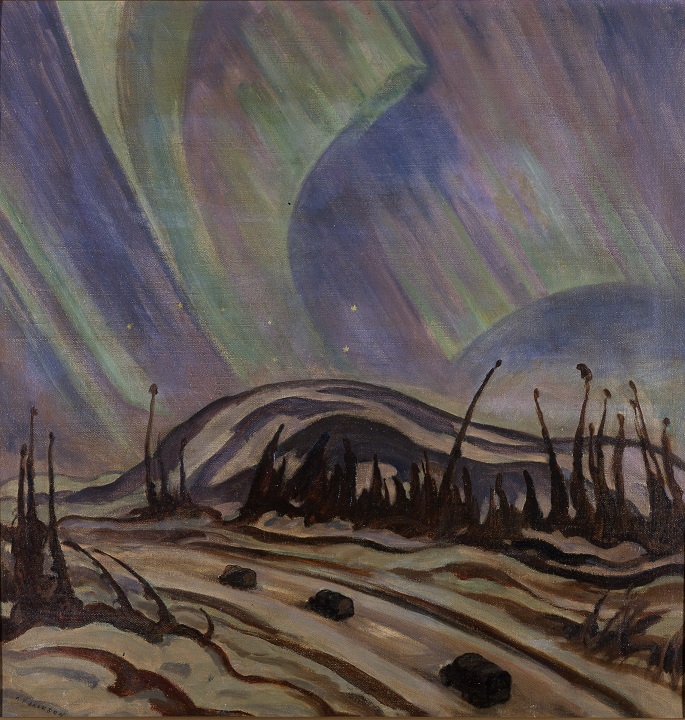

Jacques also brought our attention to an expressive painting by A.Y. Jackson of Northern Lights, Alaska Highway (1943), which is hung beside Carr’s Lone Cedar (1936). There are notable similarities with the colours and expressive brushstrokes. Could this expressiveness be due to the West Coast energy that has shaped Carr’s painting style?

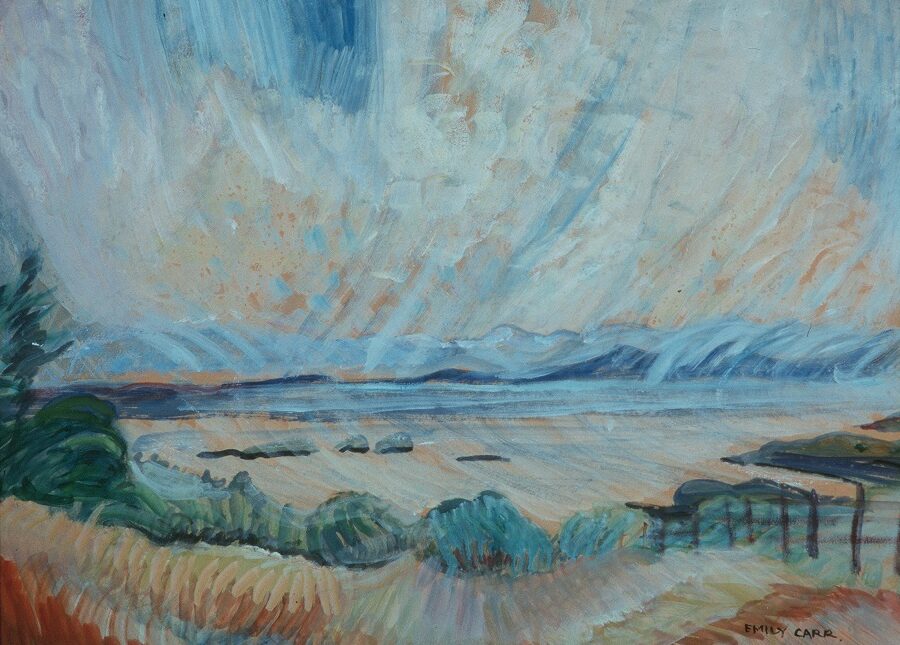

Featured above: Emily Carr (Canadian, 1871-1945) | Lagoon at Albert Head | c. 1936 | oil on paper | The Thomas Gardiner Keir Bequest

Unformable Things: Emily Carr and Some Canadian Modernists | January 19 – October 27, 2019 | Curated by Michelle Jacques | Graham Gallery