By Audrey Wang, AGGV Volunteer

Throughout history, travel has had an immeasurable impact on visual culture. Travel and landscape painting are inextricably linked, especially between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, when invention and development of new modes of transport and the increased establishment of roads, railways, waterways and cross-Atlantic sea travel, paved the way to global tourism. Later, from the nineteenth century onwards, travel and photography helped to further shape our understanding of foreign parts of the world. Over the centuries, travel took on many purposes, from symbolic pilgrimages to exploration and expansion of empire, from the elite Grand Tour to immigration and refuge-seeking, from trade to education. Considering all the different reasons for travel, this suggests that landscape painting (and later, photography) is imbued with political, social, cultural and technological significance.

When the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century halted Grand Tour ambitions and put on hold the advent of travel by the non-elite class of Europeans, new and trendy replacements were found. These included the already established Salon exhibitions of landscape painting, trendy yet inexpensive Japanese ukiyo-e prints and the panorama, an invention by Scottish portraitist Robert Barker in the late 18th century.

With travel restrictions in place all over the world today due to the pandemic, the notion of travel has become even more omnipotent. We desire what we cannot have! Charu Suri writes in an article for Architectural Digest, October 2020, entitled “Inside the Rise in Demand for Travel Art”, that “with people spending more time indoors, wanderlust has found an outlet on the walls of adventure seekers’ private spaces”, reporting brisk sales at art fairs, auctions and art galleries of travel posters and original artworks with travel themes.

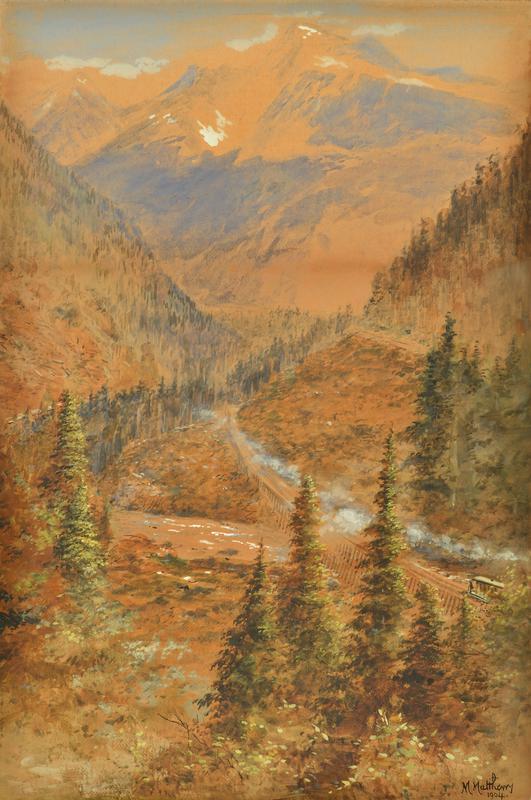

The AGGV’s art collection is diverse and travel-related artworks range broadly from the perspective of European, North American and Asian artists. While landscape paintings and prints are numerous in the collection, I have selected images specific to modes of transport which mark the beginning of travel, seeing as the journey is perhaps as important as, if not more so, than the destination.

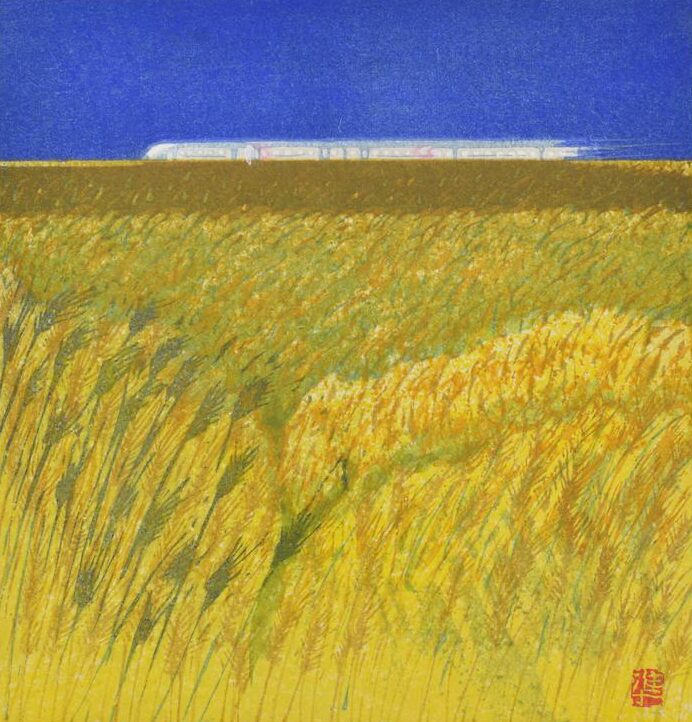

The invention of the steam train opened up possibilities in every part of the world, allowing industry and commerce to grow and making holiday destinations accessible to the masses. High-speed rail made travel more efficient. Junichiro Sekino’s woodcut (feature image) of Japan’s Shinkansen or bullet train beautifully characterizes it as a sleek and unobtrusive object speeding through the Japanese countryside.

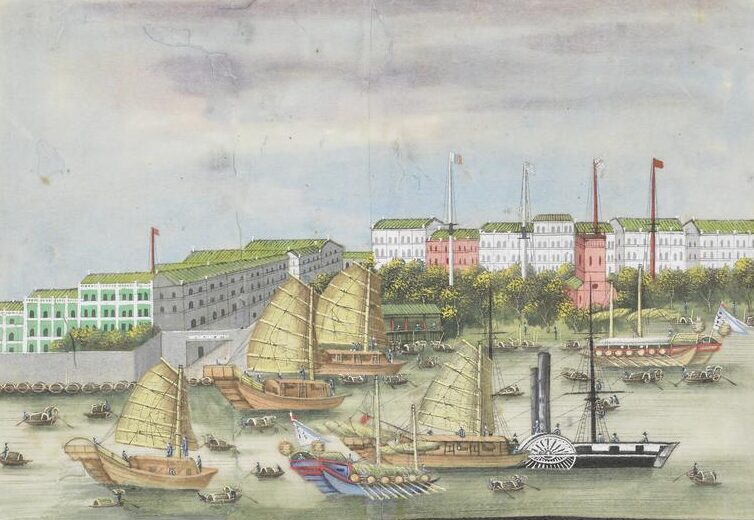

Sea travel led the way to exploration, expansion of territory and immigration. The Chinese painting above appears to show a bustling port in southern China in the mid-19th century. Such paintings were made for the export market, for European travellers to take home as souvenirs. What belies these quaint scenes is that this painting was executed during a tumultuous time in China’s modern history, signalling the ultimate end of dynastic rule. Between 1839 and 1860, the fight for commercial privileges and territorial concessions in China’s trading ports led to two Opium Wars with the British from 1839 to 1842 and with the combined British and French forces in 1856-60. Both times, China lost.

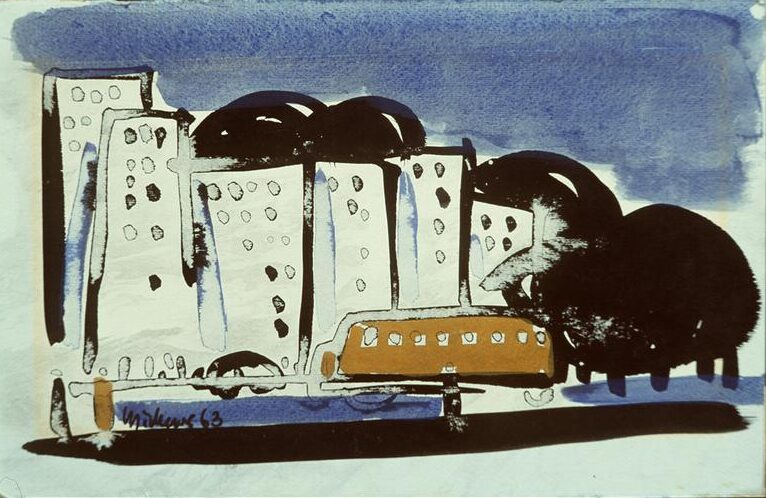

Bus tours through Europe became de rigueur among travellers from the second half of the 20th century. Artists had easy ability to cover a lot of ground through land travel in Europe and Asia, painting en plein air along the way or snapping photographs and painting from printed photos when they got home.

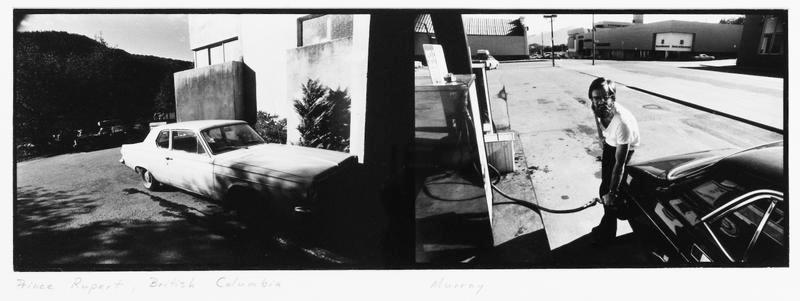

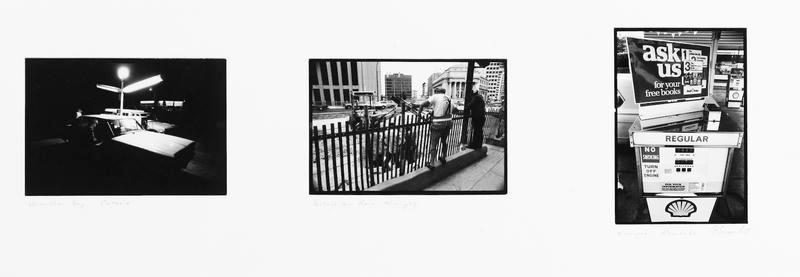

Photography captured travel memories instantaneously. Both the monumental and the mundane were caught on film. Peter Sramek documented a cross-country road trip he undertook in 1978 that took him from Toronto to Vancouver. Along the way, he took photographs of all the gas stations that he stopped at to fill his tank, thereby piecing together a photographic document of his journey. They did not comprise of anything exciting except for the fact that nearly every aspect of it was identical to the one before. In his artist’s statement, he writes:

Perhaps the cultural value of the series lies in some sociological information about getting gas, gassing up and being hooked on consumption. But tabled data to the contrary, the work is more satire than methodology. At best, one can deduce the price of gas in various parts of the country and attempt to explain the difference. One can also laugh. The images are meant for that too.

Feature image: Junichiro Sekino (Japanese, 1914-1988) | Bullet Train | not dated | woodcut | 31.5 x 29 cm | Gift of Carol Potter Peckham and American Friends of Canada (1997.046.007)