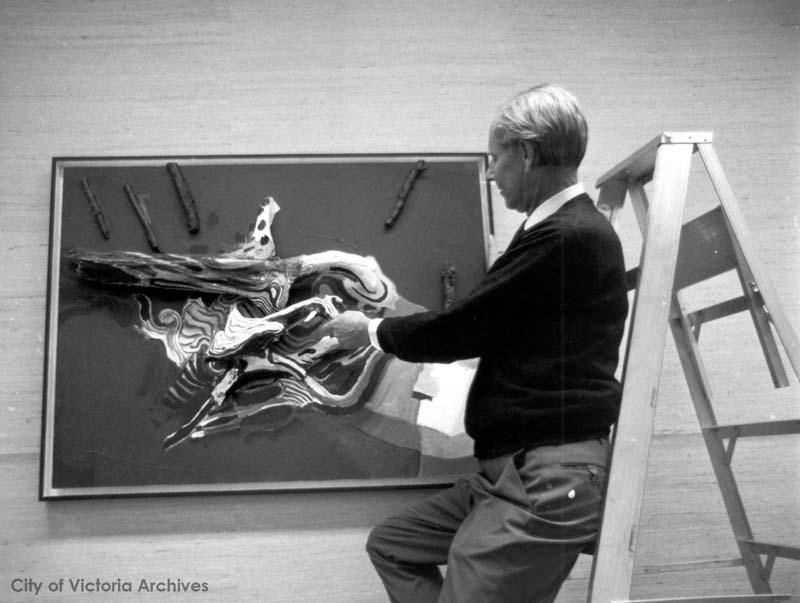

The Art Gallery of Greater Victoria presents Communities + Collections, a new program that gains insight into the diversity of our permanent collections, with the help of guest speakers and facilitators. Coinciding with the Millennia exhibition, we have invited Dr. Melia Belli Bose (pictured above) to talk about the afterlife in ancient China.

The Arts of the Afterlife in Ancient China: The Art Gallery of Greater Victoria’s Han and Tang Dynasty Mingqi

“The ancient Chinese believed that the afterlife was a continuation of life on earth; one’s identity, social status, and wealth were maintained for eternity in their tomb. Such notions underpinned China’s funerary culture for millennia and gave rise to elaborate subterranean chambered tombs that approximated the palaces deceased elites inhabited in life. Beginning in approximately 3000 BCE, the dead were buried with decorated vessels filled with food and jewelry. By the Bronze Age (ca. 2000-3rd c. BCE), aristocrats were being interred with caches of weapons, adornments and other luxury items, as well as human and animal sacrifices. An army of thousands of life-sized terracotta soldiers followed China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang Di (r. 221-210 BCE), into eternity. These costly and lavish funerary goods were functional, reminding the tomb occupant of their privileged status, enabling them to perform their duties, be entertained, and fed in the afterlife.

The philosophical traditions of Confucianism and Daoism, which gained widespread popularity during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) guided the development of increasingly elaborate memorial rituals and mortuary goods during this era. Focusing on the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria’s rich collection of lively and exquisitely detailed mingqi from the Han and Tang (618–907) dynasties, as well as later Chinese artworks in the collection, this gallery talk examines pre-modern Chinese understandings of death and the afterlife and their associated arts. Meaning “spirit object,” mingqi are tomb figurines of soldiers, entertainers, courtesans, livestock, fabulous beasts, and architecture. Often highly personal and at times humorous, these diminutive works of art reveal much more than ancient Chinese beliefs regarding the afterlife. They also offer insight into their owners’ lives: the types of entertainment privileged members of society enjoyed, the clothing they wore, contemporaneous notions of feminine beauty, and understandings of cultures with which the Chinese came into contact via the Silk Road.” – Dr. Melia Belli Bose

Dr. Melia Belli Bose is an Associate Professor of Asian Art at the University of Victoria. She was previously Assistant Professor of Asian Art History at the University of Texas at Arlington. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of California and has an MA from the University of London. Dr. Bose is the author of Royal Umbrellas of Stone: Memory, Politics, and Public Identity in Rajput Funerary Art, 2015, and the editor of Women, Gender and Art in Asia, c. 1500-1900, 2016.

Communities + Collections | The Art of Longevity and Immortality in China with Dr. Melia Belli Bose | Saturday, March 11 2017 | 2PM | Tour – Open by Donation