By Audrey Wang, AGGV Volunteer

Vera Weatherbie’s history as an artist is often overshadowed by her relationships with men and her exceptional beauty in many narratives. This is not to say that her connections with F.H. Varley (1881-1969) as her teacher and lover, and later, with Harold Mortimer-Lamb as patron and husband, were unimportant. Both played pivotal roles in Weatherbie’s development as an outspoken female artist at a time when women were still relegated to prescribed feminine spheres.

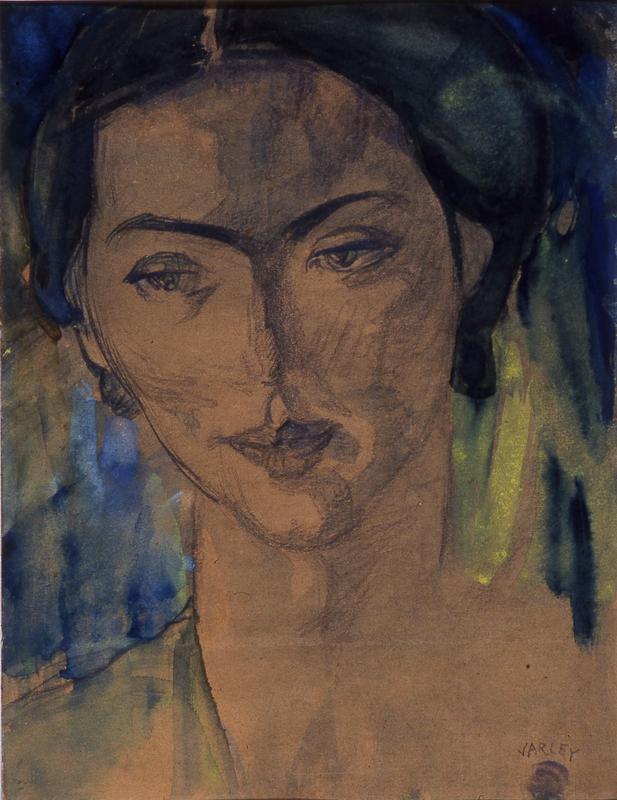

Weatherbie was born in 1910 in Vancouver where she attended the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Art (now the Emily Carr University of Art and Design) in 1926 when the school first opened. In her second year there, she met F.H. Varley who was one of her instructors and a member of the influential Group of Seven. Enthralled by her beauty and her knowledge, Varley’s relationship with Weatherbie quickly developed from teacher to friend and eventually, lover. As his muse, Weatherbie features in several portraits Varley painted (above), and vice versa. Many letters were exchanged between them when Weatherbie spent six months between 1932 and 1933 at the Royal Academy of Art in London on scholarship, and through these letters, it is revealed the intimacy of feelings between them.

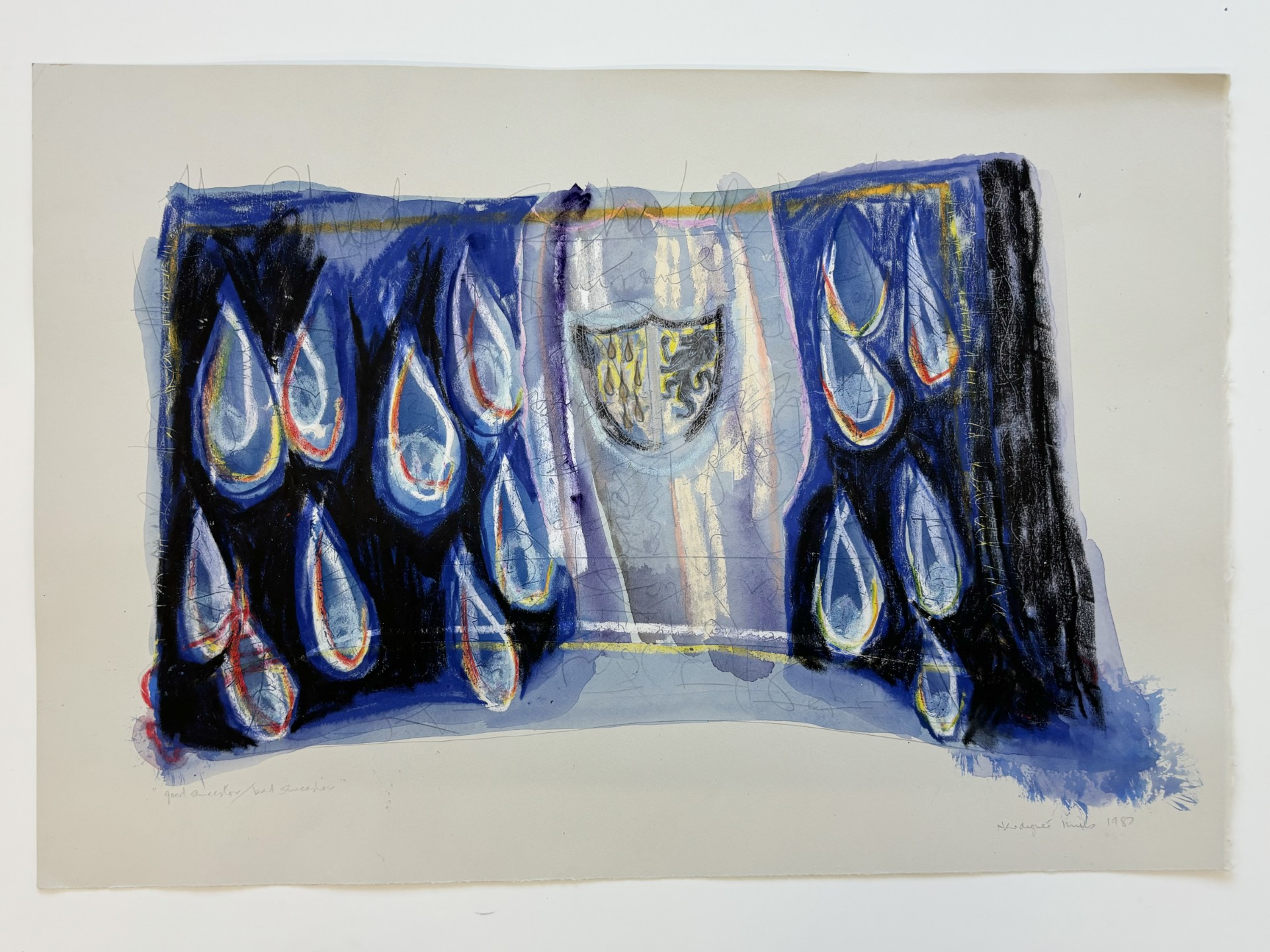

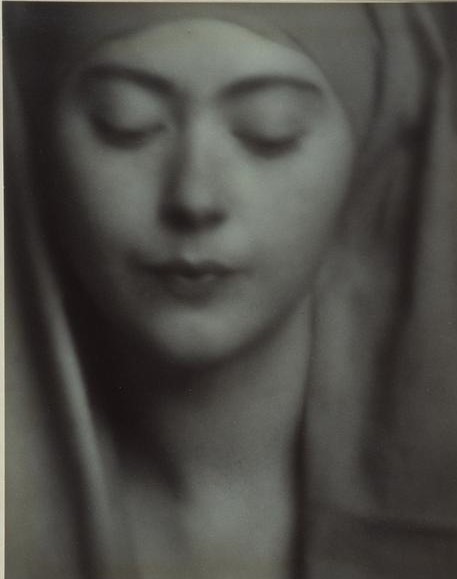

Weatherbie’s beauty was not lost on other artists. In 1929, she was invited to the studio of pictorialist photographer John Vanderpant (1884-1939) after he spotted her in a nativity play. Garbed in her costume from the play, her portrait became the ideal in the short-lived pictorialism genre of photography characterized by soft focus romanticism (above)). Vanderpant’s Gallery in Vancouver was co-owned by Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1872-1970) who was to become Weatherbie’s husband. He was also the father of Mary Bobak, a friend of Weatherbie’s. Mortimer-Lamb, an engineer and industrialist by profession, played an influential role in the development of the arts in Vancouver, acting as patron to many artists and connecting artists with each other and organizations throughout British Columbia. He was also a writer about art and a pictorialist photographer himself. The considerable age difference between himself and Weatherbie did not seem to be an issue. They remained married until his death in 1970.

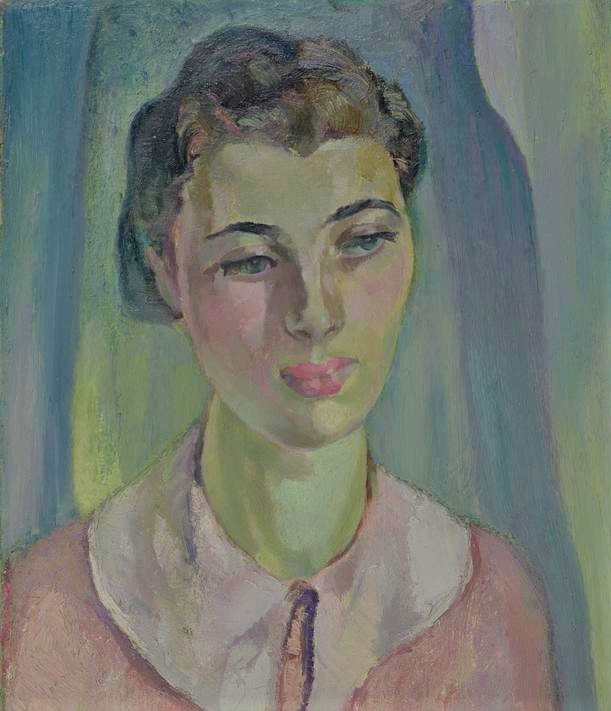

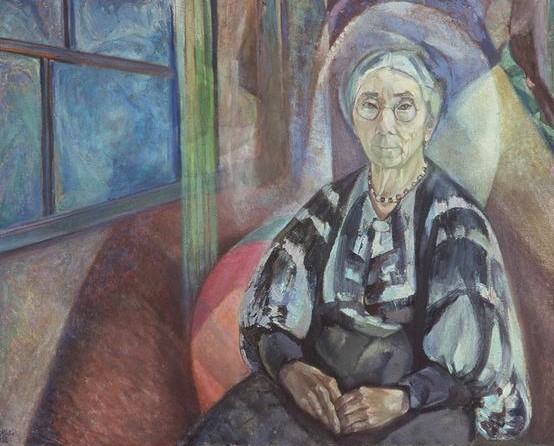

Weatherbie’s portraits and landscapes are imbued with a spirituality that sets her apart from her mostly male contemporaries. In the spirit of Canadian modernism, artists of the era embraced the various facets of theosophy, translating their spiritual connection with nature and landscape into their artworks. More than that, Weatherbie was interested in other branches of religious philosophy, educating herself in mysticism and auras. Religious elements are especially evident in the portraits that Weatherbie painted. In the portrait of Anne McKay (above), for instance, the sitter is seated on an armchair, the back of which is painted with a halo effect, suggesting the saintly qualities of Anne McKay. Weatherbie’s theosophical ideas were not limited to Christianity. A Buddha figure appears in the background of her portrait of her husband in the AGGV collection (below), balancing the composition in an almost yin-yang configuration.

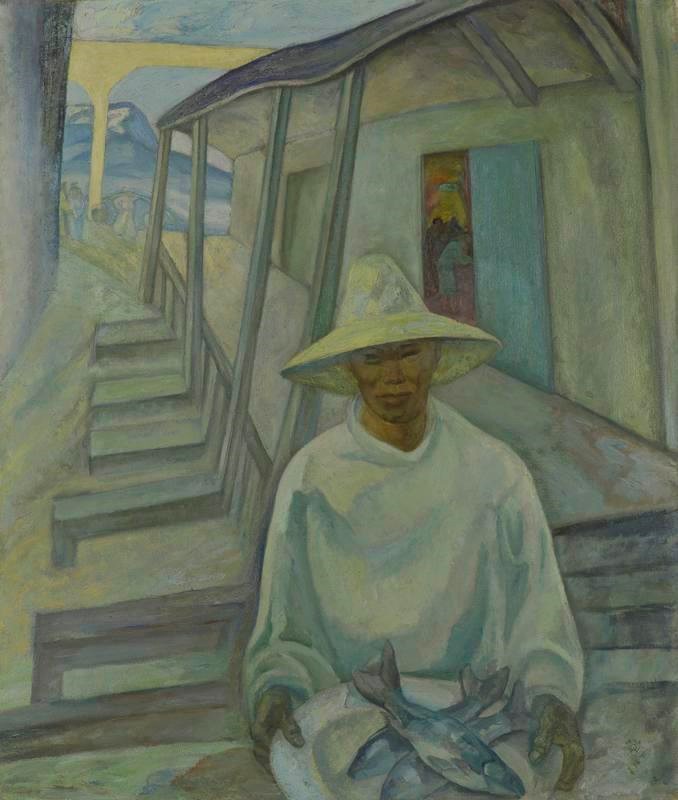

Weatherbie found some early recognition with her painting My-E-En (1934) (below). It had won the Beatrice Stone Medal for painting in 1934 and was featured on the front cover of the Vancouver Art Gallery Bulletin’s November 1934 issue. Depicting a Chinese peddler selling fish, the painting is distinctive for its feeling of mysticism. The humble man is dressed in a pure white garment, offering up a plate of fish, against a background dominated by sharp verticals and a fast-receding perspective.

Weatherbie also taught drawing and painting at the British Columbia College of Art from 1933 to 1935.

Feature image: Vera Weatherbie (Canadian, 1909 – 1977) | Self Portrait | Oil | 54.5 x 41.7 cm |Harold W. & Vera Mortimer Lamb Bequest | 1977.311.001