By Dani Neira

I took the Feminist Art Field School from my kitchen table. I’d watch the weekly conversation as I cooked myself spaghetti, have my morning coffee during our synchronous Thursday sessions, and talk lesbian haunted houses over drinks with friends. My kitchen table, a place I associate with nourishment, care, and conversation, became the intimate space through which I learned.

As a queer person, feminist, art history student, and cultural worker, I figured the Feminist Art Field School must have been made for me. The concept of conversation-based lectures that brought in different artists, curators, scholars and critical museum practitioners every week felt not only exciting, but rare. While we considered the role of the museum in social changemaking, I wondered, how are educational institutions remaining relevant to students and their communities’ needs? As an art history student, I have taken one too many classes where I type lecture notes faster than I can process them, only to regurgitate information for memorization-based exams. Michelle Jacques, one of the course instructors and a renowned Canadian curator, told an anecdote from her own experience studying art history where a Derrida-specialist couldn’t answer the simple question of “but what does this have to do with real life?”. It brings to mind the words of Black Panther’s Fred Hampton,“theory’s cool, but theory with no practice ain’t shit…”. The ways in which many professors teach theory often fail to be relevant in their lack of applicability for different worldviews. This is particularly true for students who exist outside of the structural whiteness of academia.

The polyvocality of the Feminist Art Field School unsettled any fixed notion of ‘feminism’ and created an expansive space with multiple entry-points for identification and reflection. Tania Willard’s land-based model of BUSH gallery, Sean Lee’s ‘crip horizon’, and Syrus Marcus Ware’s abolitionist framework are amongst the many practices and theories which have deeply influenced my ways of thinking and working. I was able to explore these ideas through our open-ended assignments, anchored by an overarching theme like ‘object’ or ‘place’, but spacious in format and content. I created a Tumblr cyber(space) to host my musings on identity and curation-as-care, made a zine about the possibilities of nets, and had a conversation about Institutional space and place with arts practitioner Regan Shrumm.

Somehow, Chase Joynt and Michelle Jacques—co-creators of the Feminist Art Field School—achieved (what I thought) was the impossible: intimacy in the online class. My kitchen table became the site through which I embodied this intimacy, where I could experience guest speakers be in-conversation as I cooked, ate, and thought out loud. The possibilities of intimacy as pedagogy are broad, but in the context of the Feminist Art Field School, I am interpreting intimacy as a holding of space for learning rooted in the vulnerabilities of identity, conversation, creativity, and embodiment. I am hopeful that educational institutions like UVic are making space for cross-disciplinary and partnership-based courses like this one, and more importantly, making them accessible to the public so we can all dream collectively.

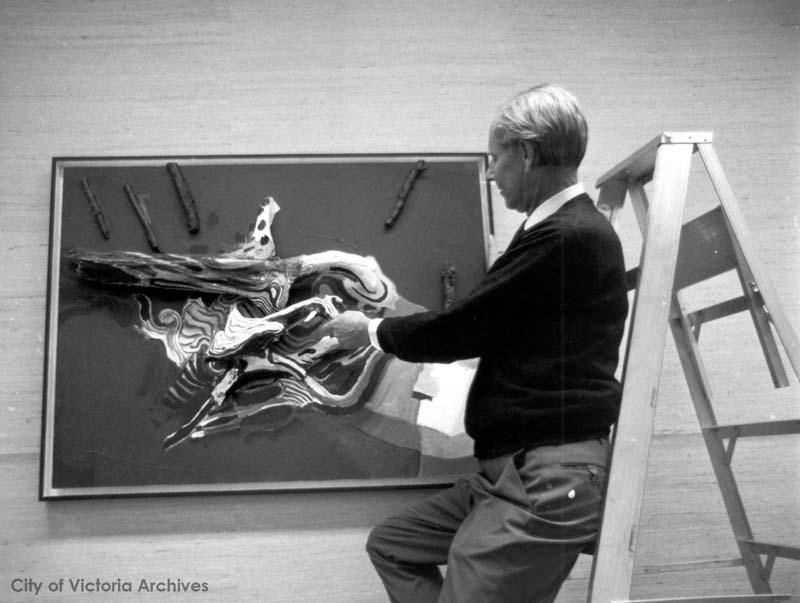

Featured Image: Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue, the entrance to Killjoy’s Kastle: A Lesbian Feminist Haunted House, 2013. Courtesy the artists.