By Nikki Sanchez

Before a global pandemic sent the world into wave after wave of lockdowns, there was a different wave of change rolling across Canada — a unified solidarity that was shutting down business as usual. It was a wave of solidarity with the Wetsu’wet’en communities of Unist’ot’en and Gidimt’en, who were under military occupation in their own territory as they stood in opposition of the Coastal Gas Pipeline. When Wet’suwet’en matriarchs called for the country to stand in solidarity with them, their call was heard from Vancouver to Winnipeg, Tyendinaga to Tkaranto.

Image credit: Nikki Sanchez, Freda Says “Reconciliation is Dead”, 2020. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the Artist.

Image credit: Nikki Sanchez, Freda Says “Reconciliation is Dead”, 2020. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the Artist.

In the Lekwungen Territories known as Victoria, an ad hoc group of youth from 34 Indigenous nations came together to take a stand that would become a historic anomaly: they occupied the Victoria legislature in prayer and ceremony for a total of 15 days before being forcibly removed by RCMP. Calling themselves Indigenous Youth for Wetsu’wet’en they released the following statement on the first day of the occupation:

“As Indigenous youth we stand with Wet’suwet’en assertion of sovereignty because we understand that Indigenous Peoples will cease to exist without our land; our languages, cultures, and future generations cannot survive without it. Indigenous youth are not only inheriting a climate crisis driven by fossil fuel projects like CGL, but also Canada’s legacy of colonization, genocide, and gendered violence against Indigenous women, girls, and Two-Spirit people. In protecting the lands from industrial development, we are protecting our bodies from violence.”

Image credit: Nikki Sanchez, Drum, 2020. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the Artist.

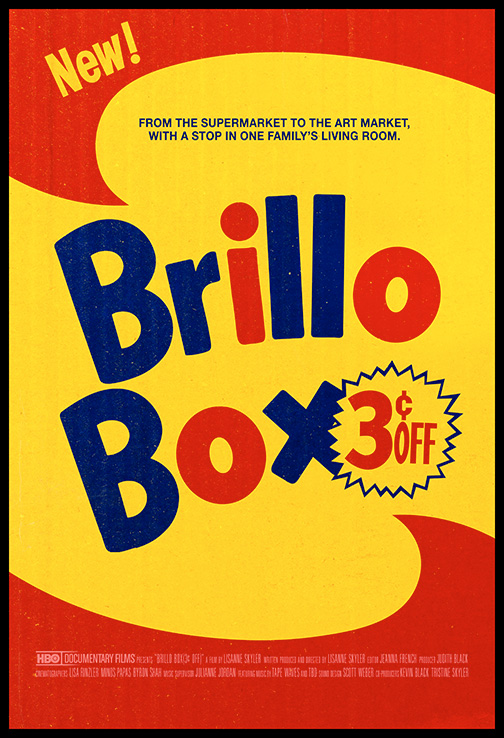

The ceremonial occupation became a community hub; hundreds of people remained present on the legislature steps through the cold and wet coastal February days and nights. It was a self-sustaining micro-community which included a kitchen, medical center, and healing tent. There were near-constant cultural activities, healing ceremonies and participatory art projects. The youth held multiple press conferences, musical performances, educational speeches and even documentary movie nights projected across a massive open air screen. While the community was coming together, Victoria Police surveilled the site around the clock. By the second week, the occupation garnered national and international media coverage. And then suddenly, Covid-19 struck and across the nation everything shut down as a result of mandatory lockdowns, everything that is, except for resource extraction.

Image credit: Nikki Sanchez, Spirit Gate, 2020. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the Artist.

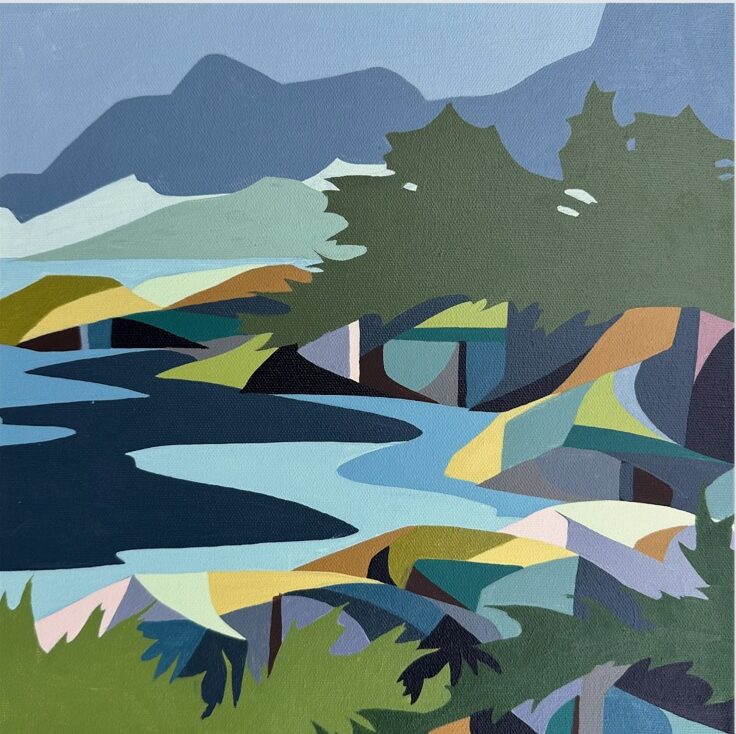

As the rest of the country had its focus entirely redirected towards surviving a pandemic, visual artist and activist Marianne Nicolson of the Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nation was not able to shake the impact of what she had seen the youth create at the legislature. She decided to take action and reached out to Nicole Stanbridge, a friend and collaborator who is the Curator of Engagement at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. Together they explored how art and activism could intersect to foster the resiliency of spirit that had been shown by Indigenous Youth for Wetsu’wet’en. What emerged was a year-long process of collaborative creation, an intergenerational residency and art exhibition. Marianne and Nicole collaborated with Tla-o-qui-aht artist Marika Swan and myself, a Pipil and Irish/Scottish educator and activist. What emerged was a sacred process of healing, community building and recognition for the generations of activism to protect and maintain Indigenous ways of life. From this a six month residency was born that brought together twelve Indigenous artists/activists to share, heal and imagine together, guided by peer-led cultural teachings.

Image credit: Nikki Sanchez, Decolonial Love, 2020. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the Artist.

The culmination of this residency is the Holding Ground exhibit, a multi-media exhibit that tells the story of Indigenous resiliency, resistance and excellence through the lens of participants Gerry Ambers, Aya Clappis, Ace Harry, Lisa Kenoras, Laura Manson, Jessica Mayhew, Feather Nault, Ross Neasloss Jr, Stephanie Papik, Coral Shaughnessy-Moon, Nabidu Taylor, and France Trepanier, as well as the contributions of facilitators Marianne, Marika, Nicole and myself. At the center of this exhibition is a curtain designed by Marianne Nicolson and collaboratively made by members of the group. As Marika explains, “This anchor… allow[s] us to create our own microcosm of the universe. Within this we can re-enact the nature of our inter- relationships with each other and to the land. In community, each generational role is necessary. Isolated, we are vulnerable. But in formation we have great strength in the diversity of our offerings.”

Holding Ground is on until October 17th. The community is invited to come and engage with the incredible stories and legacies that are shared. Our hope is that visitors will be able to locate themselves within the legacies depicted in the exhibition and reflect on their personal responsibilities to the people and places of these unceded territories.

Featured Image Credit: Nikki Sanchez, A Generation Rises, 2020. Digital photograph. Courtesy of the Artist.