By Audrey Wang, AGGV Volunteer

December 13, 2021, marks the 150th anniversary of Emily Carr’s birth. Beyond this commemoration, the AGGV’s exhibition Emily Carr: Seeing + Being Seen features artworks that carry significance that is as relevant today as they were nearly a century ago when they were first made.

Carr drew inspiration from her surroundings, depicting the West Coast landscapes in and around her hometown of Victoria and around Vancouver Island and British Columbia during her travels. The exhibition asks viewers to consider how she had chosen to represent these places and indirectly, her acknowledgment of the Indigenous peoples who were the stewards of these lands. The exhibition also asks us to reflect on Carr’s status as a settler in the lands of the Lekwungen-speaking peoples, and how that has impact on her choice of subject-matter and whether her artworks should be taken at face value or as examples of cultural appropriation.

Emily Carr’s travels to remote Indigenous villages in British Columbia and in Alaska provided a subject-matter that is often regarded as a historical documentation of place and culture. Devoid of people, the three watercolour paintings of totems in the exhibition – Totem Walk at Sitka (1907), Big Eagle, Skidegate, B.C. (1929) and Angidah Naas River (not dated) – takes the artist’s (and by extension, the viewer’s) perspective from a respectful distance and from below, allowing the totems to tower over us and be admired as an integral part of the treed landscape.

Carr’s interpretation of these cultural icons imparts a sense of awe and respect, but it also brings to question how such subjects would have been represented by an Indigenous artist, instead of a colonial settler. The significance of place and the familiarity with one’s own culture can draw on a different insight.

In the large scheme of things, 150 years may not seem such a long time, but Emily Carr’s paintings of places familiar to those who live in the traditional lands of the Lekwungen-speaking peoples, may look significantly different in the century or so since these landscapes were painted. A video in the exhibition gallery highlights the many local sights that Carr painted over the years. An early painting from 1905 depicts a very different Victoria Inner Harbour. Other paintings of well-known places around Victoria compel the viewer to decide how much or how little has changed in that place.

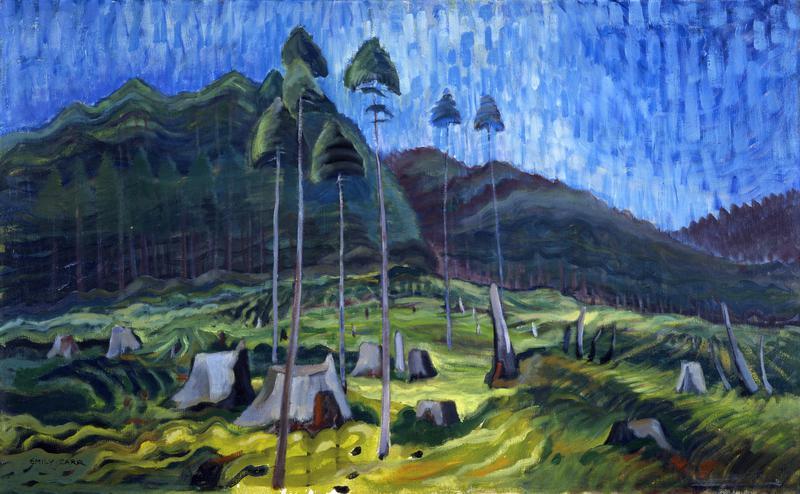

Carr’s love for the British Columbian landscape is evident in the painting Odds and Ends (1939), even in a scene that for some viewers might seem compromised – that of a clear-cut forest. Here, stumps in the clear cut forest rise above undergrowth. However, the sadness is contrasted with the uplifting verticals of the left-over seed trees, the vibrating sky, and the undulating brush strokes of the forest backdrop, all of which celebrate Carr’s spiritual connection with nature.

transferred to the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria (1998.001.001)

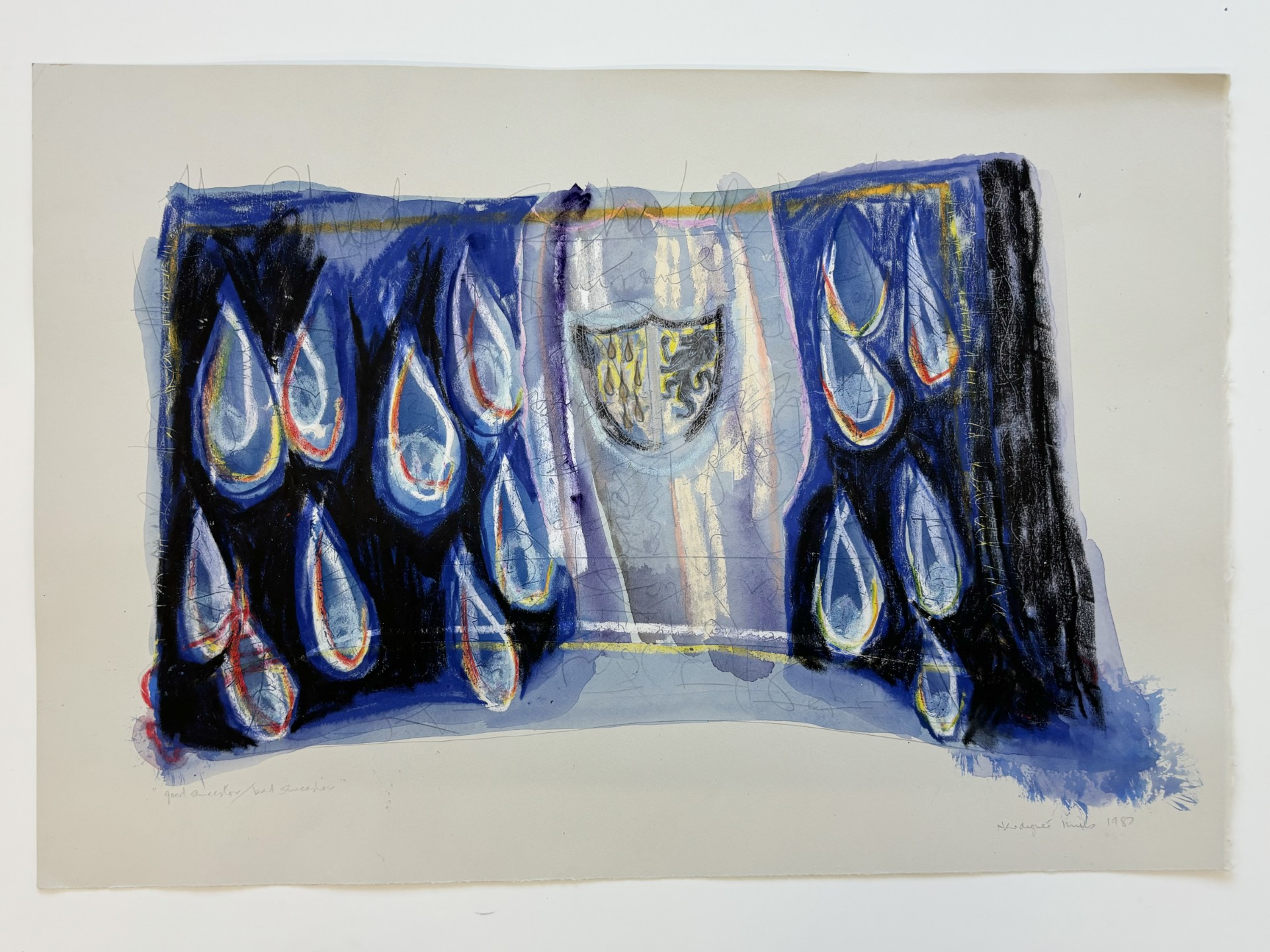

Also included in the exhibition are artworks, photographs and writings by other artists who were in some way or other touched by the legacy of Emily Carr. Showcased are artists such as Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher, Pat Martin Bates, Jack Shadbolt, Isabel Hobbs, and Joan Cardinal-Schubert, all of whom see Carr through their own unique vantage point, and contribute to the ongoing discussion about what her work and legacy represent. The lens through which artists are seen by others shapes their legacy throughout their lives and after they are gone, and Emily Carr is one case in point.

Feature image: Emily Carr | Totem Walk at Sitka | 1907 | watercolour | 38.5 x 38.5 cm | The Thomas Gardiner Keir Bequest (1994.055.004)

Emily Carr: Seeing + Being Seen | Graham Gallery | July 17, 2021 – July 17, 2022 | Co-curated by Mel Granley and Nicole Stanbridge