By Mel Granley, Guest Curator

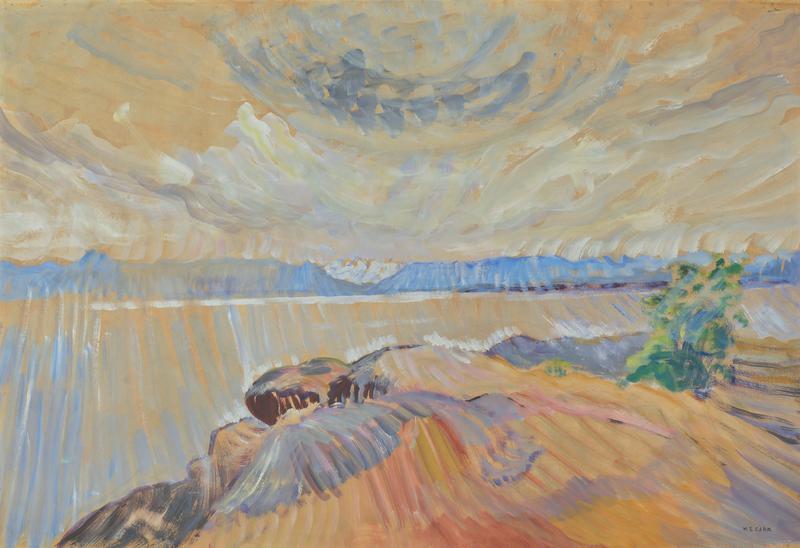

Art galleries and museums have been grappling with their role as political institutions over the last few decades, after centuries of positioning themselves as neutral hubs of expert knowledge. Emily Carr has become almost synonymous with the Pacific Northwest; her work being displayed year-round in different exhibition contexts to ensure the satisfaction of visitors to the AGGV. This drive to see her work is directed by the idea of checking off a list of great and thoroughly known artists within the artistic canon. The issue? The “art canon” is heavily Euro-Western centered and very keenly demonstrates a bias for settler-European art, while largely failing to acknowledge the artistic merits of historic and contemporary BIPOC artists. Carr’s work being displayed annually is a prime example of this.

As an Indigenous curator and person, it bothers me that this artist whose career is built off of the voyeurism and oppression of Indigenous peoples is given the most space each year. Those spaces could be used to hold BIPOC lead shows, such as the tender and thoughtful work of the exhibition Holding Ground that happened this past summer.

Galleries and museums are not neutral spaces, art is not neutral, and the time period and context does not excuse the content and harm perpetuated by those works. In this time of truth and reconciliation, I would ask settler readers to think about their position here, why they value Carr’s work, and why a gallery space should be held annually to represent the antiquated settler ideals of the 19th and 20th centuries. These questions can be difficult to grapple with when first confronted with but change in thought and action are rarely easily had.

Kischii maarsii (thank you very much),

Michif and Ukrainian settler