By Audrey Wang, AGGV Volunteer

The AGGV exhibition, Blue & White, is a wonderful demonstration of cross-cultural exchange between China and the rest of the world, through a singular commodity – blue and white porcelain. In this article, we will look at how the European market affected the production of porcelain at Jingdezhen, the centre of porcelain production in China, in the late Ming period (16th/17th century).

The arrival of the Portuguese in China in the 16th century marked the beginning of organized trade directly with China. The commodities that affluent Europeans sought in Asia included spices, tea, textiles and porcelain. This search for luxury goods was the prime mover in the creation of an integrated world economic system as we know it today. In Europe, porcelain was a status symbol that was used as tableware and as ornamentation. The European appreciation for Chinese porcelain likely stemmed from the technical perfection of the porcelain body.

The culture of collecting in Europe is evident in the vast quantities ordered in the 17th century. It is also during this period that the porcelain cabinet or ‘China closet’ made its appearance as a fashionable decorative piece of furniture in stately homes and country estates. Before long, the material culture of China became subsumed in the history of these grand interiors.

It is not clear when the mass production for export ware was first started, but it’s likely that once the Chinese merchants realized the potential market for porcelain in Europe through the Portuguese traders, large numbers of wares began to be made for European customers. This fine porcelain demanded first by the Portuguese, then by the Dutch, is called Kraak, named after the carracks which carried them to Europe. For more about Kraak ware, read “10 Things To Know About Kraak Ware” in this issue of the e-magazine.

The entrepreneurial initiatives of the Chinese merchants were crucial to the development of Jingdezhen as a centre for porcelain manufacture, particularly after imperial orders came to a halt following the death of the Emperor Wanli in 1620. The palace could no longer afford to spend money on luxuries like porcelain, as all available funds were concentrated on military efforts against the invading Manchus. New markets were sought in the domestic sphere as well as overseas, and here, merchants became increasingly influential in their capacity as middlemen. A money-based economy quickly evolved following the arrival of the Europeans on the Asian trading network, and a new class of rich merchants emerged, consequently creating a market of discerning local Chinese patrons for fine porcelain.

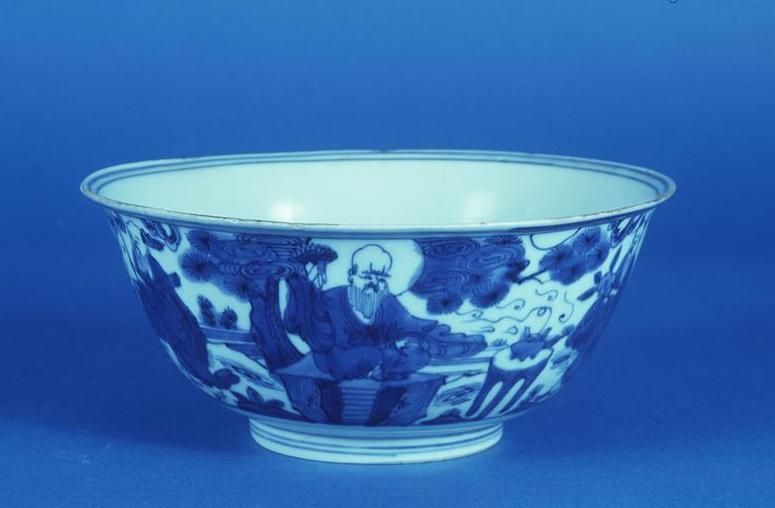

As more wares began to be made for the domestic market, as well as for Japan, we find the emergence of new stylistic features including new styles of landscape design, a boldness in brushwork, tonal contrast and composition. Unhindered by the court’s prescribed designs, the potters were free to experiment. There was a proliferation of narrative themes gleaned from popular novels, dramas, poems and legends, with designs adapted from albums of woodblock prints and book illustrations which circulated among the literati and the growing number of literate people.

Prior to 1640, conventional shapes helped to identify which market — domestic or overseas — porcelain wares were made. However, this distinction became blurred in the 1640s as attractive and useful shapes became absorbed.

The cross-cultural currents flowing between Asia and Europe are hugely significant. With maritime trade, the great distances between continents closed in, and exchanges in cultural understanding, economic proceedings and political ventures were made possible. In trade, porcelain held great influence. As a commodity, it brought work and wealth to China, and a new luxury good to Europe. As a work of art, it promulgated cultural exchange, with Europeans absorbing Chinese styles and vice versa. The importance of the European market is undeniable.

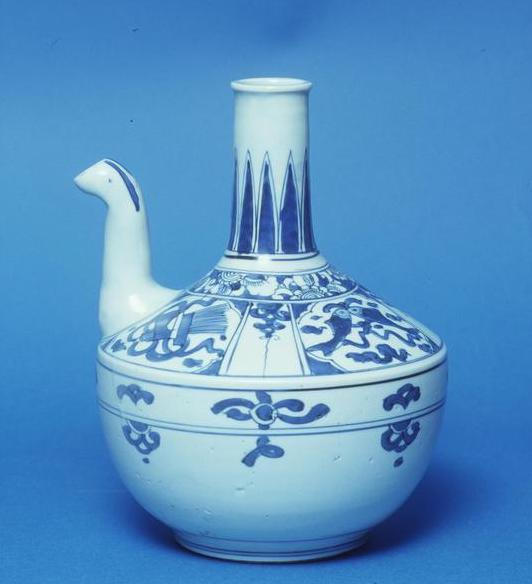

Feature image: Blue and white Ewer with Buddhist Emblem of Fish | Chinese, 17th century | Gift of James & Joanna Davidson (1997.059.008)

Blue & White | January 30, 2021 – January 30, 2022 | Curated by Heng Wu, AGGV Curator of Asian Art and Michelle Jacques, Head of Exhibitions & Collections/Chief Curator Remai Modern