Persimmon Blackbridge is an innovative Canadian artist, writer, and activist, who rocked Vancouver in the early 80’s with ground-breaking works exploring lesbian sexual politics, disability culture and mental health.

Blackbridge continues to break barriers today with a major new show touring multiple Ontario cities: Constructed Identities. The show features a large collection of small hand-crafted figures made from wood, metal, and found objects and the artist aims to reshape the meaning and aesthetics of disability as disruptive and satisfying.

Constructed Identities was also the opening exhibition of Tangled Art Gallery (2016), Toronto’s first accessible gallery space dedicated to enhancing opportunities for artists with disabilities. The exhibition opened at the Âjagemô Gallery at the Canada Council for the Arts (2018), and more recently, at the Gallery in the Woods on Hornby Island (2019), where Blackbridge resides today.

We recently caught up with the artist about her influence on disability culture, what she thinks about feminism today, and her interpretation of the two works of hers we have in the AGGV collection (featured in this article).

AGGV: You were quoted in a 2005 interview with the Society for Disability Arts and Culture saying that you find meaning in making art that lessens the sense of isolation and shame just by talking about your disability in public. Throughout your career, have you seen any changes in the conversation surrounding disability in Canada?

PB: Oh tons! There was not much conversation around disability and art when I started out. At the time, I didn’t identify as disabled, but disability had really defined my life. I had a learning disability, and my alcoholic father beat me for not doing things right. So even though I was white and middle class I was seen as a person who could not go to college who could not make a career for themselves. The question is so huge… it feels like so much has changed since I started doing art.

AGGV: You mention that even though a disability was affecting your life you didn’t necessarily see yourself as a person with a disability when you started out in your art career. Can you elaborate on that?

PB: “In my life, disability was always something that you hid from people. In my family, my father was an ex-mental patient and that was definitely hidden from people. I hid my learning disabilities from people because I knew it made people treat me like I was stupid. I hid my own psychiatric history from people because I knew that would make people doubt my perceptions and reactions, it makes you a person who’s not taken as able to speak for themselves or understand what’s going on around them. It took me quite a lot longer than it took me to come out as a dyke to be able to go: “Okay, I have a learning disability” and “Okay, I have a psych history.” A couple of people, Geoff McMurchy among others, confronted me and said: “you’re in the closet about being disabled and we would like you to not be in the closet about being disabled.” That confrontation really helped me realize I wasn’t helping anyone by being in the closet. I was just continuing what I grew up with, which was shame and hiding. And so, I’m really grateful for that.”

During Blackbridge’s earlier career, her work explored Canadian prisons and psychiatric institutions from the patients point of view — both from her own experience as an outpatient and in collaboration with others including ex-inmates. Her first major collaboration, Still Sane (Women in Focus gallery, 1984), was inspired by the experiences of Sheila Gilhooly, a lesbian forcefully institutionalized in the 1960s on account of her sexuality. The exhibition was a sculptural and written account of Gilhooly’s experience incarcerated in the hospital. The text of the show (written on the sculptures) would later inspire a revolutionary survival narrative by Blackbridge and Gilhooly, published in 1985 by Press Gang. The book, also titled Still Sane, was highly revered and swept through feminist communities.

AGGV: Can you share some insight on the Still Sane collaborative project with Sheila Gilhooly in the mid ‘80’s? What was your experience like?

PB: “Yeah, before I “came out” as disabled, I had done a lot of artwork that was around disability. I worked with Sheila Gilhooly on an art show (Still Sane) which later became a book. I was using her words and my sculpture as kind of like a sculptural memoir about the three years she spent in and out of mental institutions for being a lesbian. She and I would talk really openly together about our very different experiences of the psych system, but my experiences were always safely hidden and hers were out in the open.”

AGGV: So, you were almost dealing with the subject as a writer would in the third person, by using Sheila’s story as a vehicle to talk about institutionalization without having to bring yourself into it?

PB: “Yes, and after Geoff talked to me I started the project Sunnybrook, which was an art show and then a book. It was about people in Woodlands institution, but I called it Sunnybrook so that I wouldn’t get sued or anything. It was about my time working at Woodlands and the institutionalized people I met there and their struggles with that incredibly awful and abusive place. But I also talked about myself as a person with a disability within the context of that. Sunnybrook showed how much privilege I had relative to the institutionalized people, but also indirectly showed a lot about people with invisible disabilities and how we learn to lie and hide in order to not be in the position that more directly targeted people are. Sunnybrook is simple on its surface, but it’s quite complex looking at a lot of different kinds of disability and a lot of different ways that people are taught. And it’s also about my experience as a worker within an abusive institution and about how no matter how good hearted or sympathetic you are, if you’re working within that institution it’s your job description to carry out abuse on people. It’s so easy to get sucked into the dehumanizing institutional perspective that allows people to treat other human beings as if they don’t count. So, Sunnybrook was a real shift for me in terms of being open about my own position in these things, my own privilege, my own lack of privilege, my own culpability, my own struggles to come to terms with it.”

AGGV: Do you think by making art about disability, you’re reclaiming a kind of agency by being the person who is able to investigate disability instead of rendering yourself as an object to be studied?

PB: “Yes! And because I wasn’t naming my own position in Still Sane and a later series working with four women who had been in prison about their experiences, I was often cast as this kind of artist/social worker who was bringing forward the stories of these poor unfortunate people. It was hard on Sheila and me because it put us in these roles that we didn’t have personally with each other. We had to figure out ways of fighting the roles people assumed we held. These unspoken assumptions were all around us. No one was outright saying: “Oh yes well, you are more sophisticated that Sheila because you are an artist and she’s just a poor little mental patient.” It’s not spoken, it’s just the assumption that underlies all questions. To learn how to interrupt the assumptions rather than answer the questions, that was really tough and that was a lot of what brought me to do Sunnybrook. I felt like I couldn’t do work from that position and the only way to deal with that was to tell my own story.”

AGGV: Do you think coming out with your disability empowers Still Sane in retrospect? That it stops pathologized readings of the book?

PB: “Yeah, I think it does. I also think Sheila has written more about her experience and dealt in depth with the gender issues that were happening in her experience. She wasn’t really institutionalized because she was a lesbian, it was because she was a butch lesbian. She’s written really beautifully about her understanding of that complexity. People just can’t see her any longer as this one-off person who I helped. She’s a strong Canadian voice.”

During the 80’s and 90’s, Blackbridge was also a member of Kiss and Tell, a Vancouver based art collective together with Lizard Jones and Susan Stewart. The group formed out of a larger meeting of feminists in 1984 who had gathered to discuss pornography. The collective used debates about lesbian sexual politics in the queer community to fuel their works. Most notably, the collective’s bold and controversial interactive photo exhibition Drawing the Line (1990) toured internationally asking viewers to draw the line when they found images of lesbian erotica disturbing. This body of work was recently celebrated at the 25th anniversary of the Queer Arts Festival (Vancouver, 2015) to highlight the historical significance of how the collective used their work to propel the feminist and lesbian movement forward.

AGGV: What changes have you seen in the feminist and lesbian rights movements since you began your career? Do you see renewed interest in the work that you were doing now that there’s this third, fourth wave even?

PB: “I feel like people like to know that we have history. Second wave feminism was a battleground and sometimes it gets identified with certain ideas, but those ideas were constantly being fought. Second wave feminism wasn’t just a bunch of white women ignorant of their privilege. It was also black women fighting and changing that. There’s a reason why things changed and it’s because people were fighting. People value knowing that. They value seeing the fighting that was happening the middle of the highest strength of the anti-porn movement in second wave feminism, that there was questioning of that, that there was fighting of that. And that fight is still continuing, and third wave feminists are still fighting that fight. The anti-trans sentiments that come out of certain segments of the feminist movement are really devastating. Here in Canada we can think of it as a marginal position, but in England it’s a very strong movement. And in the States trans rights are being just decimated!”

AGGV: You talk about the value in looking back at progressive work that was made during the second wave of feminism. In a way, you highlight the importance of realizing that there’s still a lot of work to be done today – that it’s not a narrative of simple linear progression.

PB: “Yeah, and in disability art as well. I get to be the old dyke auntie of the disability movement because I was doing disability art is the 70s and in the 80s and 90s. It feels a lot like there’s a new focus on disability art and there’s a new audience for disability art. But we’ve been around for a long time and we’ve been speaking for a long time. We’ve been singing and shouting and crying for a long time. I think that’s something that is valued in my work, that y’know I’m old! I like that, I’ll take that. You know, I meet people who I admire. Like the disability scholar Eliza Chandler in Toronto and she goes; “Oh, I studied you in school!” and I go “Oh! Okay well, now you know I’m just a normal fool, but I’m glad that it was something that made you feel more able to speak your truth in a way that was harder for me.” Because I didn’t have that representation.”

AGGV: Do you find a kind of justice in being able to provide that for others?

PB: “Yeah! Yeah! Throughout my life there’ve been people just opened doors for me. Like the Vancouver artist and writer Sky Lee was the first person I ever saw who put text on her drawings. She put political–– personal political–– beautiful, evocative writing all over her portraits and it was just like “Oh my god!” That’s something you can do?!” and that opened so many doors for me! If I can do a little bit of that for someone else, then that’s awesome.”

AGGV: That’s an incredible story. It also connects art to activism, in that you have those moments of “Oh! I didn’t know you could do that!” Did art come first to you, or activism? Or were they always tied together for you?

PB: “*laughs* They were always tied together for me. I started making art, though I would never have called it art, when I was having a major breakdown. The guys around where I was all had like carving tools and they carved wood. I started using my boyfriend’s carving tools to do properly domestic things like bowls and spoons and stuff because I couldn’t be an artist because I wasn’t someone who could draw inside the lines of coloring books. I was too messy, too all over the place. But the act of carving helped lessen the pain for a few minutes, a few hours while was working on it. I started doing it more and more, and eventually, I came out. I kicked out my boyfriend. I kept his carving tools. This is when I was like 19. I kept carving things and I was starting to understand my life from the perspective of being a woman and all the things I was told I couldn’t do. My craving got more and more complicated and less and less domestic and then I had to say: “Okay, what am I doing?” And I had to say art. It was too late to say: “You can’t do art, you’re not one of the people who are allowed to do art,” because there I was doing it. I slid in through the back door. That is disability, queerness, feminism all tied into my starting to make art. All those things have always been tied in together in the whole process of saving myself from my condition at the time. I continued to do art with a lot of focus and a lot of passion because it was my bulwark against going to that bad place again.”

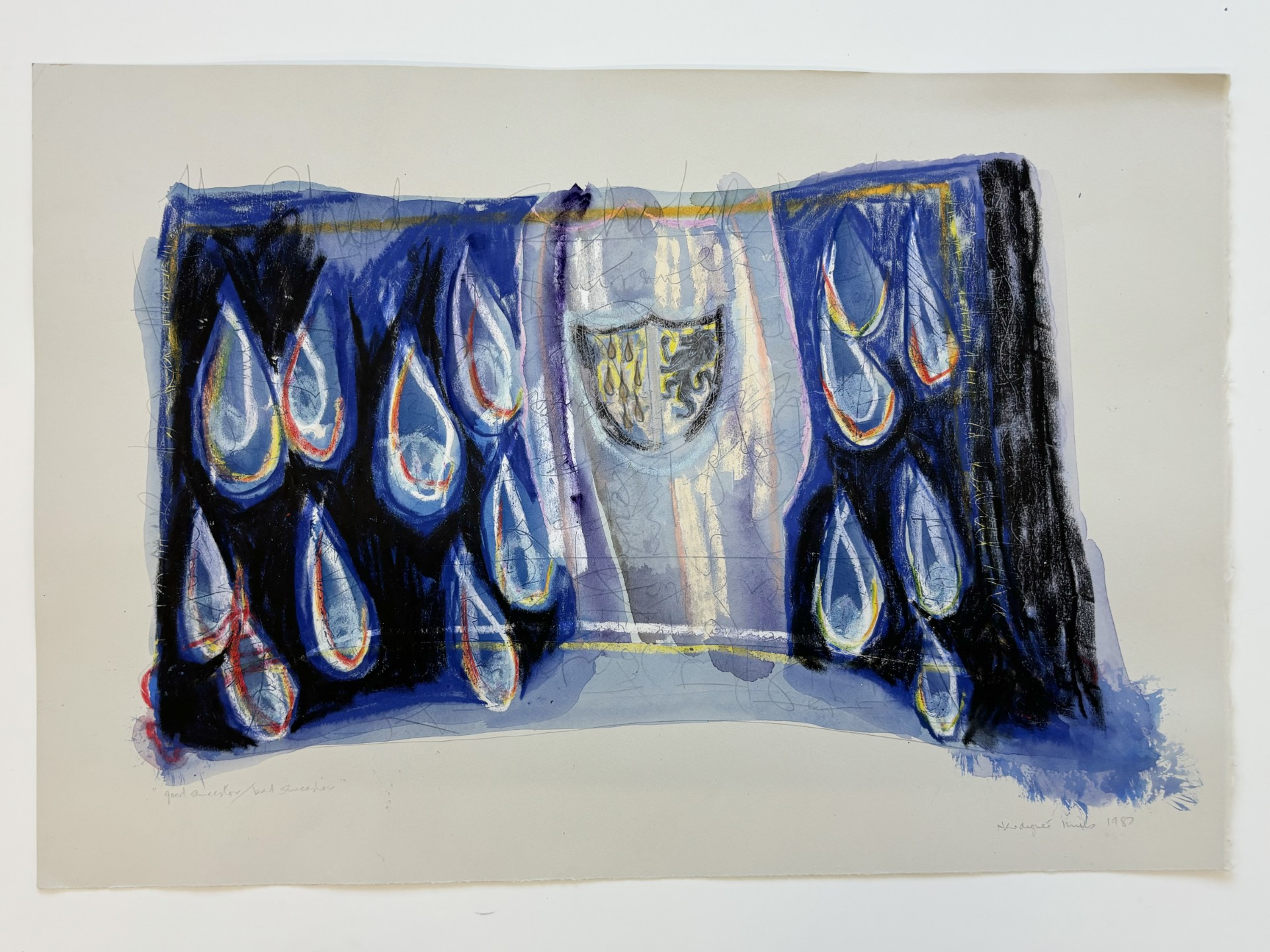

AGGV: Well, we have one last question for you about two works of yours that are in the AGGV collection: ‘Fire Eater’ and ‘Fire Jumper’. What was your interpretation of them when you created them and how would you interpret them today?

PB: “It’s interesting because that was way back in my life as an artist. I’ve always appreciated the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria for buying pieces from me that early in my career, I was just out of art school. I’ve always been drawn to figurative representation and I was doing work at the time on acrobats and circus performers. They were all women portrayed as strong and adventurous and leaping through fire and stuff like that. You know, it was the 70’s and it feels a bit cliché now but at the time it was stuff we weren’t seeing. There was both a feminist portrayal of strong women with a lot of joy and wildness about them, but it also tied into coming out and not feeling like I had to make a number of sculptures of men at the same time in order to like not to let anyone know. It’s not only about myself, it’s also about my desire and my gaze. So that was part of my liberation and being able to go: “Okay, I’m going to portray women and not worry that people are going to think that I’m a dyke because I am a dyke so there.”

Blackbridge has been awarded the Ferro-Grumley Fiction Prize, the VanCity Book Prize, the Lambda Literary Award, the VIVA award for visual arts, and the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design Distinguished Alumni Award. Her art has been shown across Canada and the U.S., as well as in Australia, Europe, and Hong Kong.

Feature image: Permission Blackbridge, Fire-eater, earthenware; oil paints, 20.5 x 32.5 cm, 1981. Peter Cotton Memorial Fund. 1981.219.002