By Jon Tupper, AGGV Director

What’s really happening when people encounter art? How does it affect them? It’s a mystery researchers have pondered for centuries. Here at the Gallery, I think of visitors regarding Emily Carr’s towering west coast forests; or an intricate Japanese print; or the ghostly digital trees in an installation such as Kelly Richardson’s The Erudition, which appears in our current show Supernatural: Art, Technology and the Forest. Any casual conversation after such encounters would reveal that art can affect people’s moods, stir memory, even cause chills or other bodily sensations.

But until recently, hard science paid little attention to emotional, physical and even subconscious—or “pre-reflective”—responses to art. Western society’s understanding of how people engage with works of art was, for much of the 19th and 20th centuries, based on the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s ideas about aesthetics. Namely, that a viewer experiences an artwork through intellect alone. Now, a burgeoning branch of 21st-century brain science known as neuroaesthetics is starting to change that.

This melding of expertise in neuroscience, philosophy and, in lay terms, art appreciation, has its skeptics. How can we, for example, use digital images of the brain to understand or define beauty? Well, maybe we can’t. But neuroaesthetics researchers are learning that brain injury or illness can inject exciting changes into an artist’s work: knowing this gives researchers clues to follow, which may ultimately help us understand how elements of the brain influence creative activity.

Scientists are also learning that when we’re taking in a dance performance, say, the cells in our brain responsible for the movements we’re witnessing activate, mirroring the dancers’ moves in our minds. Called “mirror system theory,” this may explain why seeing a dancer execute a soaring leap across the stage may give us a jolt of joy, or we may grow agitated watching a dancer hop frenetically through a scene. The parts of the brain responsible for social perception and engagement have kicked in: our own emotions are amplified as we “experience” those of others, simply by seeing them expressed through movement.

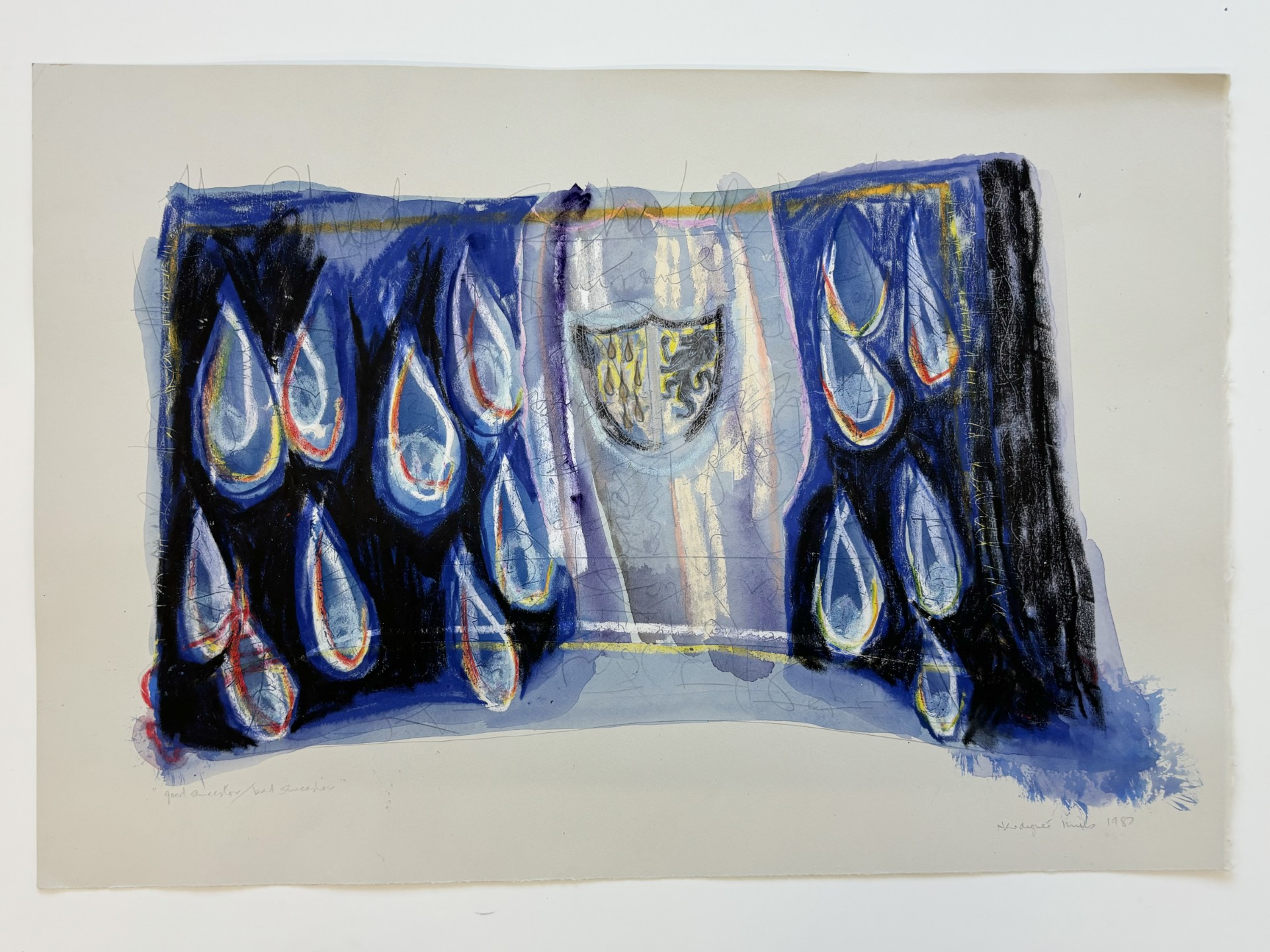

Image above: Performance artist, Judith Price, moving to the brush strokes of Emily Carr.

Other researchers are comparing the reciprocal interaction between viewers and artworks— for example how having our senses engaged by an artwork may point to its meaning—and what happens when, in day-to-day life, we experience another person’s subjective perspective. In other words, the relationship between encounters with art and empathy.

At a time when the arts increasingly need to fight for their rightful place in education, I find this new field of research particularly exciting.

At the Gallery, we understand, by our own direct experience, the value of our popular Family Sundays and Studio programs.

We know that when we invite families into the gallery on Sunday afternoons to paint, make collages, design buttons, put their mark on a mural—or any number of messy, hands-on activities—that we’re not just firing creativity in kids, we’re bringing groups of actively creative minds together in a conducive social environment.

We know that when we bring artists into schools, or children into the studio and the galleries to engage with works of art in all disciplines, and to learn the techniques to try making their own, that their minds are creatively stimulated and energized—but it isn’t just their minds that are involved.

We know these activities are valuable. They bring people of all ages from different walks of life together. They encourage positive interaction among children, and between children and adults. Eyes light up, ideas are exchanged, experimental impulses expand, and confidence blossoms.

Maybe soon the field of neuroaesthetics will be able to tell us just what’s happening in the brain as the glue is globbing and the scissors are snipping and the brushes are dipping and conversations flow. That deeper scientific understanding of the value of art education can only help us make the case for bolstering its foundations and furthering its reach.

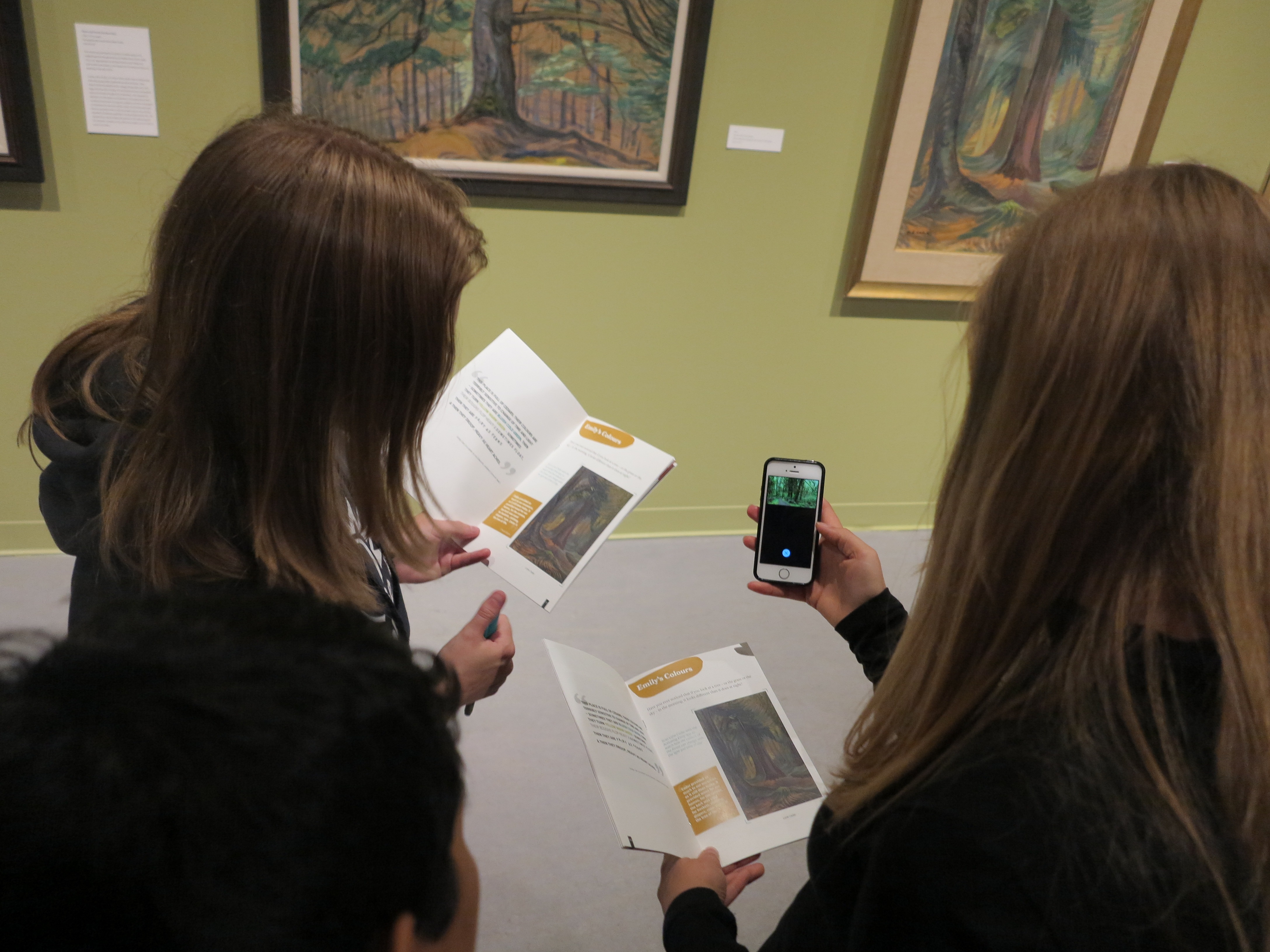

Feature top image: Visitors experiencing Emily Carr’s work via “Activating Emily“, the AGGV’s new app and activity book available for free download iTunes.