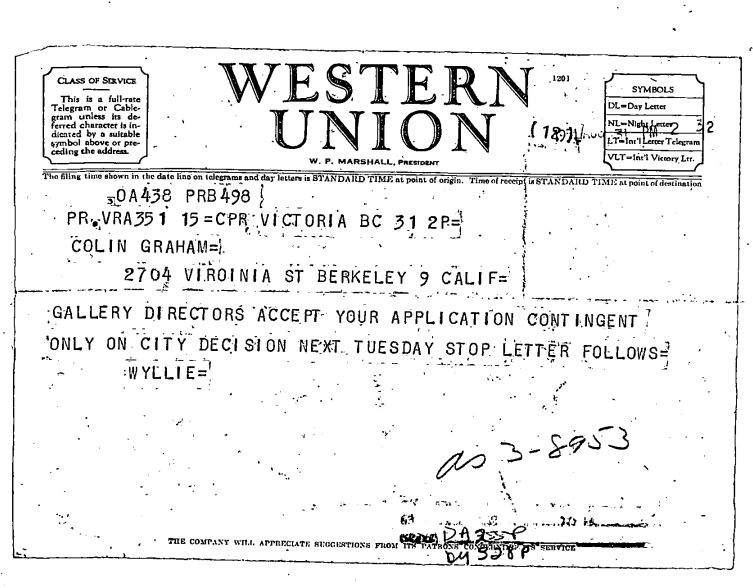

In spring of 1951, 36-year-old Colin Graham wrote to Ina Uhthoff, then Convenor of the Exhibition Committee for the Arts Centre (the Centre would formally change its name to the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria in 1955), inquiring about positions in art education in BC. Educated at the University of British Columbia, and later Cambridge and the University of California at Berkeley, Graham was initially a Medieval historian whose interest in modern art arose after viewing an exhibition by the Group of Seven. Graham had taken painting lessons from Uhthoff in 1945 when he visited Victoria, and they had remained friends. That year Graham had also met [founder of the movement which created the Art Gallery] Mark Kearley for the first time when he was invited to the St. Andrew’s Street studio of Emily Carr. Carr had passed away several months earlier and this visit was arranged by Kearley and Lawren Harris to survey the works in her possession at the time of her death. Although Graham lived in California where he was Director of Education at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, he was born in Vancouver and wished to return to British Columbia to be closer to family.

When Uhthoff responded and encouraged Graham to apply for the role of Director/Curator he was intrigued by the challenge of making the Art Gallery a vital and forward-looking part of the city’s cultural life. His 1945 visit to Emily Carr’s studio impressed upon him that a modernist instinct was present in Victoria, albeit hemmed in by a lack of support by its few cultural gatekeepers – Victoria remained stubbornly in the Edwardian age. Graham was frank that he lacked any administrative or curatorial expertise, and his ambition was to teach, not govern. It also weighed on him that this role would shoulder immense responsibility. He wrote to Uhthoff in July, “The position is a crucially important one. The person who takes it on can take no half measures or be lukewarm about it if he is going to make anything of it at all. If the centre does not get off to an efficient and impressive start, it would be doubly difficult to gain momentum later.”

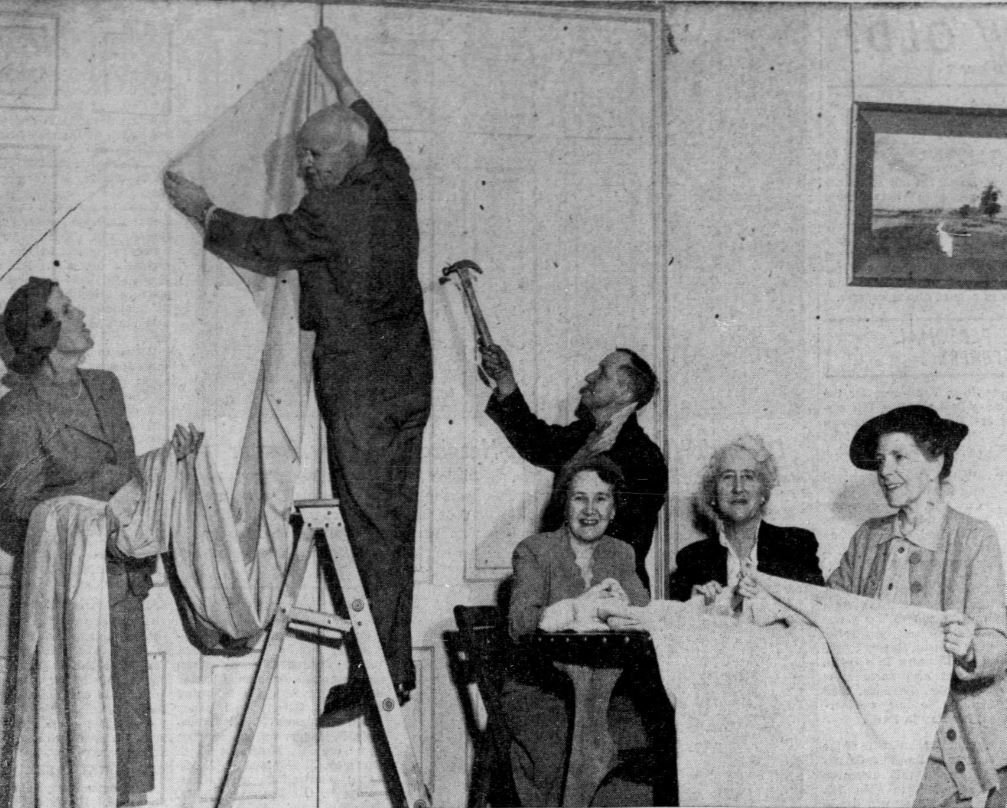

In accepting the position, which he did in September 1951, he qualified that this would be a temporary endeavour of a year or two while the Gallery established itself in its new home and until an appropriate teaching position opened up for him elsewhere in the region (Graham would stay on as Director until 1973). That fall, Graham and his wife Sylvia moved into the Spencer Mansion, for a time living alongside Sara Spencer until her new home in Cadboro Bay was ready. Graham’s staff was comprised of himself, a part-time secretary, and a part-time handyman and guard, the latter a retired wall-eyed Alberta farmer who lived in the mansion basement. The mansion’s stately main floor drawing rooms (now the Spencer Gallery and foyer) were converted by Board members and volunteers who sewed and hung curtains as a backdrop to paintings and performances. The first large exhibit was a survey of the Quebec avant-garde (Riopelle, Mousseau, Borduas).

The show had been scheduled before Graham’s arrival in Victoria, but it was an indicator of the direction he wished to head. As Graham later reflected, “In those days I could not count more than ten people in Victoria who had any grasp of what had happened in the art world since the death of Van Gough and Cezanne.” Ruffling audience feathers and upending expectations delighted Graham. He believed that an art gallery should have a place in community life and that modern art appreciation was of national value in that it depicted what was actually happening in society. Graham was adamant that Victoria was deserving of such a place. In the 2009 catalog, Vision Into Reality: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria Early Years, 1951-1973 published by the AGGV in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name, both former AGGV Chief Curator and the late artist Michael Morris wrote about Colin Graham’s tenure at the AGGV (which lasted decades longer than he initially intended). I recommend this publication (available in the Gallery Shop) for an overview of the AGGV’s history and Graham’s role in shaping its permanent collection and curatorial vision (in addition to anecdotes about Graham sleeping overnight in the galleries to guard valuable art works and crawling out an office window to avoid a chatty donor).

Graham wrote in1951, “Art is not just a pleasant luxury in civilized life, the icing on the cake, but an absolute fundamental necessity to any well-functioning society, and in the broadest terms it should be the basis of early education, not just an added frill.” A central goal of the founding movement of the Gallery was to educate postwar Victoria residents about modern art, to distinguish itself from groups like the conservative Island Arts and Craft Society, said to be stuck in reverence of past artistic movements (Emily Carr referred to some of the watercolours produced by these painters as “anemic”). In the early days of the Little Centre, Mark Kearley was walking through Beacon Hill Park with his children when from behind a bush jumped a waxed mustachioed member of the Society, pointing his riding crop at Kearley and berating him for his modernist agenda, “You, Sir, are the upstart Kearley, are you not? You with your Emily Carrs, Renoirs, and Picassos; we have no need of you in this town!” A few years on when Graham took up his position, attitudes had not changed significantly. With his background in teaching he established an inspired studio program that would introduce children and adults alike to art appreciation that emphasized free thinking, lack of restriction, experimentation, and self-discovery. This approach would allow for regard of the old masters while stimulating an openness to contemporary practices.

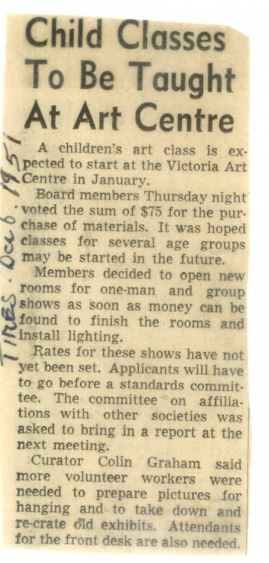

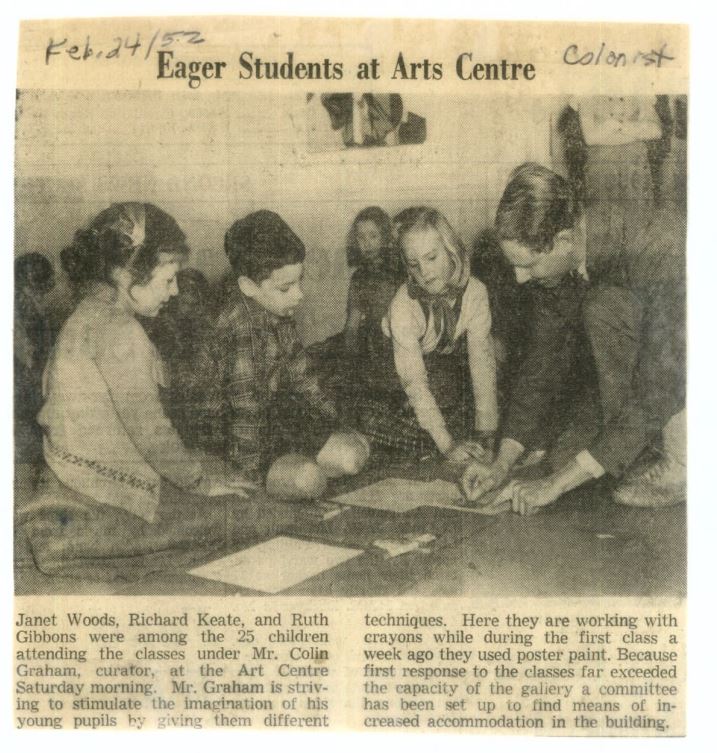

When the Art Gallery opened its doors to the public in late 1951, Graham taught a handful of Saturday morning art classes to children, often assisted by Ina Uhthoff. Adult classes were also offered early on, with Uhthoff teaching a “businessman’s art course” developed to relax the harried modern professional. Long lineups on registration day evidenced huge demand for classes, to the extent that classes had either to expand or be cancelled entirely due to lack of resources. Thankfully funding was received from the Association of Childhood Education and a Provincial Government education grant, and by May 1953 numerous art and handicraft classes were available to children aged 2-16, as well as adults. Registration fees were kept to a nominal level so that no child need be excluded for lack of money.

That year saw 150 registrants each week and modern artists Jack Shadbolt and Jan Zach were among the instructors. All classes were held at this time in “The Children’s Art Gallery” – two former bedrooms converted into an airy studio on the Mansion’s second floor. Even this space was not expansive enough, as it was not uncommon for art making to extend to the Mansion stairs and landing. Activities such as these, alongside exhibitions, film screenings, creative writing courses, regular performances by local music, and dramatic arts companies all enlivened the building. Graham recalled his aim was to “have so many things going on at Moss Street that if things reached a crisis point financially there would be too many people involved to let it crash.” But beyond this practical purpose was his belief that Canadian galleries should be active centres of living art not merely “mausoleums entombing the achievements of the past.” Concurrently Graham was writing a regular Art In Review column for the local newspaper, the Victoria Daily Times.

– Written by Anu Henderson, AGGV Administrator, Curatorial and Learning & Engagement.

Stay tuned for Part 4: Colin Graham’s role in educating the wider community about art while also making the case for increased civic support to maintain Gallery operations.

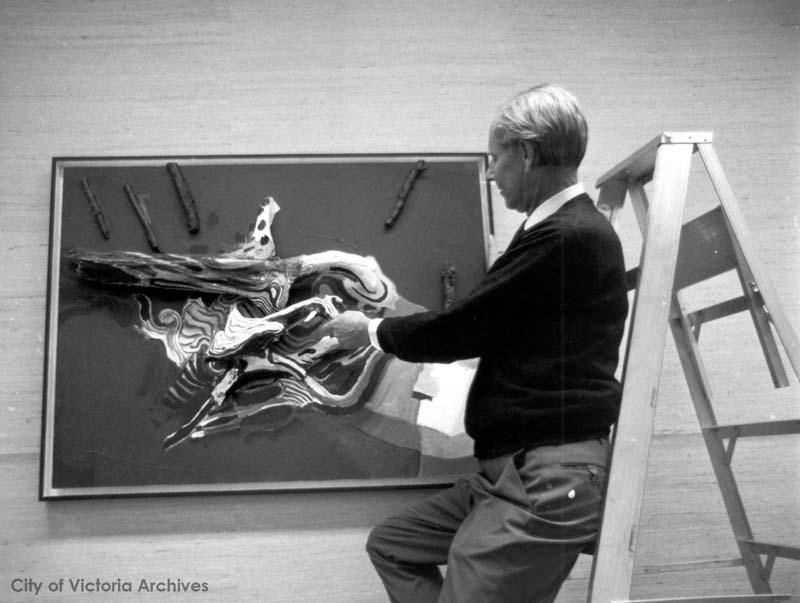

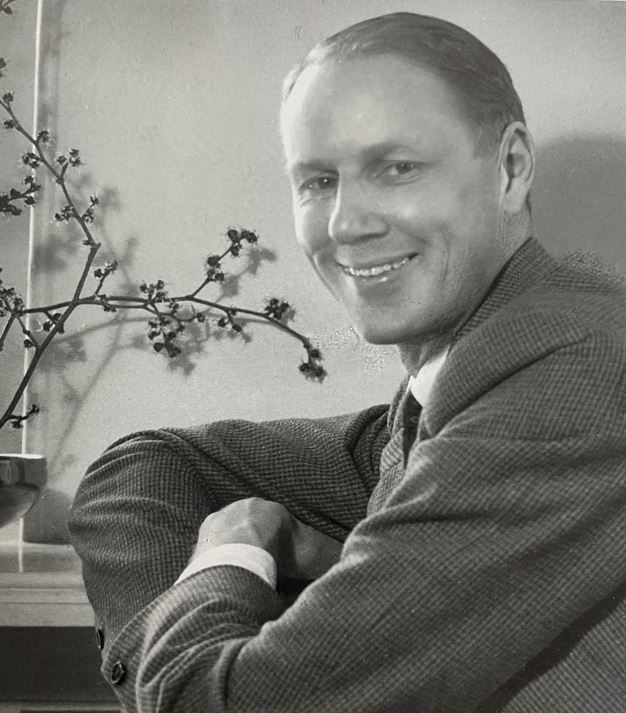

Feature Image: Colin Graham, 1968. Photo by John Williams. Courtesy of City of Victoria Archives.