By Audrey Wang, AGGV Volunteer

The exhibition Point of Contact: On Place and the Westcoast Imaginary centers on a pertinent part of Vancouver Island’s modern history, the story of Captain James Cook’s arrival in 1778 and his role in opening up trade at a place the colonists named Nootka. On a more personal level, the exhibition was put together by the AGGV’s curator Haema Sivanesan as a way for her to explore the history of the island and to better understand what it means to live on Indigenous lands by looking at the juxtaposition of Canadian (colonial) art history and Indigenous history.

Captain Cook landed in the village of Yuquot on Nuu-chah-nulth lands. Through a series of miscommunication, the colonists gathered the place was called Nootka, and thus named it as such. Featured in the exhibition are anthropological engravings by British explorers, contemporary works by Nuu-chah-nulth artists and artworks by non-Indigenous artists.

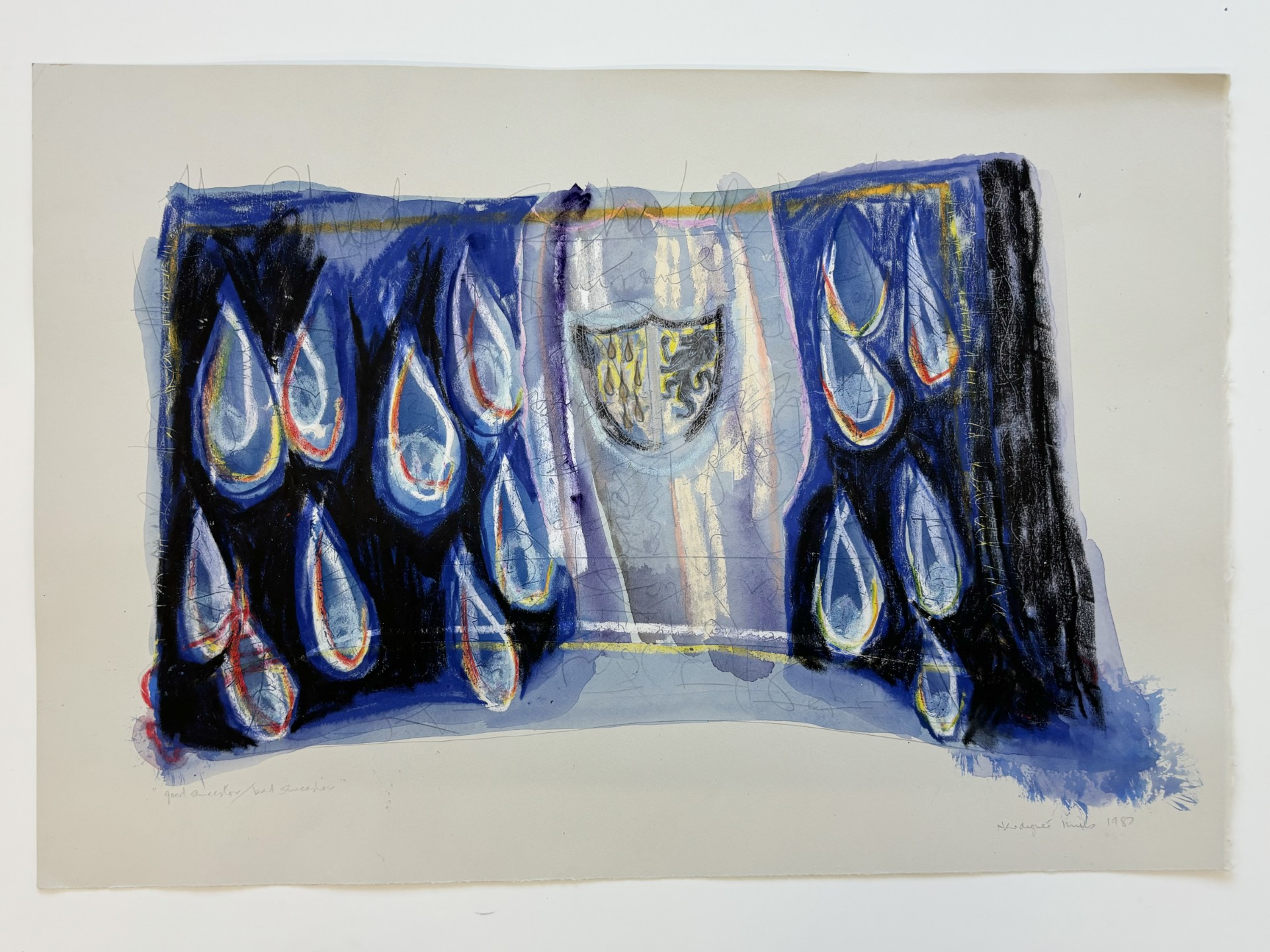

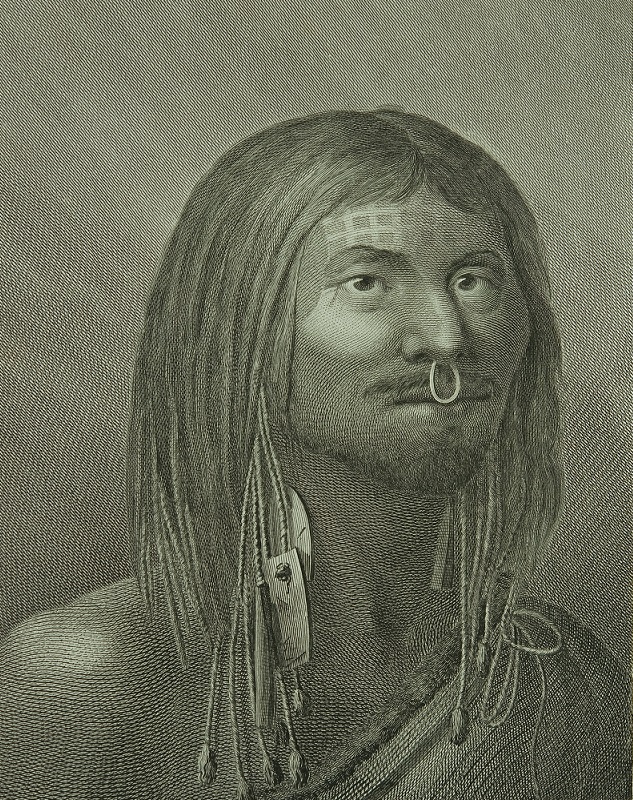

Haema’s Curator’s Tour last November began with observations of engravings by English artist John Webber (1751-1793) who accompanied Captain Cook on his third Pacific voyage. Webber’s drawings and paintings here observed the local peoples and the landscape, comprising part of the official account of Cook’s expedition. These were some of the earliest images of this part of the Pacific to be circulated, and they captured the imagination of artists, poets and writers of the time. Haema urged participants to consider the accuracy of Webber’s renderings. She pointed out that the images were created from the perspective of the sea, or from the outside. By contrast, later renderings of Nootka were drawn from the land looking out towards the sea, that is, from the inside looking out. Jock MacDonald’s three paintings, in particular, show the insider’s view. The artist lived in Nootka in the 1930s and painted the community’s everyday life.

The video installation in the next room by Stan Douglas features overlapping readings of a fictional text by two male voices representing the British and the Spanish colonists. The Indigenous voice is a deliberately glaring omission from this work, and in response to this absence, the AGGV commissioned the longhouse construction by Nuu-chah-nulth artist, Hjalmer Wenstob. The massive structure is the anchor of this exhibition. Haema pointed out that all the exhibited works refer back to this central installation.

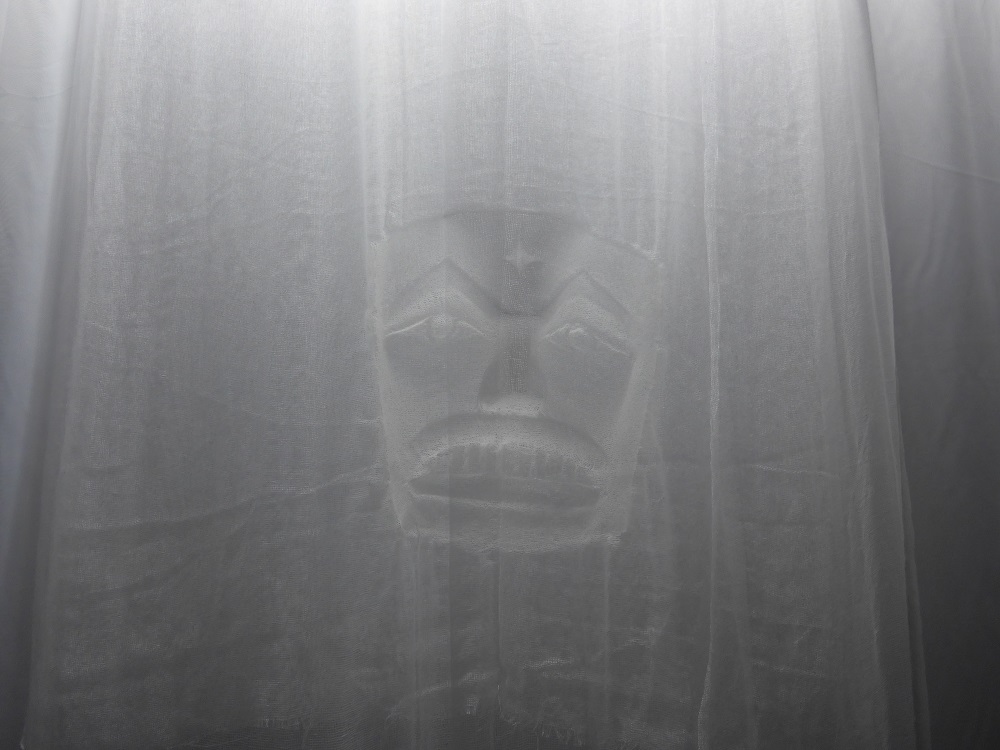

Wenstob’s longhouse is a replica of the original Yuquot Whaler’s Shrine which was filled with carved human forms, human remains, and whale replicas. It was a site of ritual purification for the Nuu-chah-nulth hereditary whaling chiefs. In 1904, the shrine was removed and acquired by the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where its components remain stacked in the museum’s vaults, yet to be displayed. Wenstob’s homage to this shrine reflects on the loss of significant aspects of Nuu-Chuh-nulth culture, questioning the role of the museum, and what the act of preservation really means.

Inside the reconstructed Shrine is an ethereal mask starch-moulded onto flimsy linen cloths. While the moulded image was clear and distinct when it was first mounted for the exhibition, it has deteriorated over the several weeks it has been on display. The original mask was traded with Captain Cook, and this again refers to the loss of cultural memory. Although not directly reiterated, Wenstob’s ensemble questions museum ethics on the sensitive subject of repatriation of cultural relics.

Point of Contact: On Place and the West Coast Imaginary | October 28, 2017 – April 1, 2018 | Curated by Haema Sivanesan | Founders and Drury Galleries