Looking for a Good Ancestor and the accompanying studies (Study for Looking for a Good Ancestor; Good Ancestor/Bad Ancestor; Good Ancestor/Bad Ancestor II; and Good Ancestor/Bad Ancestor III), as well as a self-portrait, I am not a Tourist. Are You?, demonstrate Ann Newdigate’s life-long engagement with her position as a settler, in both South Africa and Canada, in conjunction with her dedication to tapestry as a formal and discursive medium.

Born in 1934 in Makhanda, South Africa, Ann Newdigate’s personal history played a fundamental role in the subject matter of her art practice. She came from a settler family who had arrived in South Africa as part of the British Government’s 1820 Settler Scheme. This significantly shaped her life and her artwork, frequently addressing her experiences growing up in Cape Town, South Africa during Apartheid, witnessing the violence, and actively participating in the anti-Apartheid movement concerned with human rights and social justice, and working for the Progressive Party. As a result, Newdigate, along with her husband John Mills and son Julian, left South Africa and arrived in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in 1966. Prior to her departure, Newdigate received a Bachelor of Arts in 1964 in African Studies and English Literature. After a near fatal illness, she refocused her time and completed a second degree from the University of Saskatchewan in 1975, this time a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting and Printmaking, after which she was drawn to textiles and began teaching herself to weave. Newdigate pursued deeper technical study in tapestry weaving with a year at the Edinburgh College of Art followed by a Master of Fine Arts in 1986 from the University of Saskatchewan focused on tapestry. Newdigate and her family moved to Hornby Island, BC, in 1999.

For Newdigate, tapestry weaving equally embodies both the medium and its histories. Within this entanglement, the physical act of weaving reflects movement from one positionality to another (Newdigate 1995, 174). “I work in tapestry primarily for its materiality,” she stated in her essay “Kinda art, sorta tapestry: tapestry as shorthand access to the definitions of languages, institutions, attitudes, hierarchies, ideologies, constructions, classifications, histories, prejudices and other bad habits of the West.” She continued, “and [for] its capacity to shift within traditions, to shuttle between theoretical positions, to hover around borders, to challenge hierarchies and to connect with many different resonating imperatives” (1995, 174). As her exploration of tapestry deepened, this observed oscillation extended to important developments in her practice as an artist, disrupting and subsequently foregoing the divide between craft and fine art and, at the same time, coming to a greater understanding of the colonial systems that shaped her own subject position.

“I became able to name my situation and map my various contexts as a white woman in the northern and southern hemispheres of colonial enterprise, and thus could better understand the ambivalences and uncertainties of shifting identities with the two colliding spheres of art” (1995, 178.)

– Ann Newdigate

Reference: Ann Newdigate, “Kinda art, sorta tapestry: tapestry as shorthand access to the definitions of languages, institutions, attitudes, hierarchies, ideologies, constructions, classifications, histories, prejudices and other bad habits of the West,” in New Feminist Art Criticism: Critical Strategies, edited by Katy Deepwell (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), 174-181.

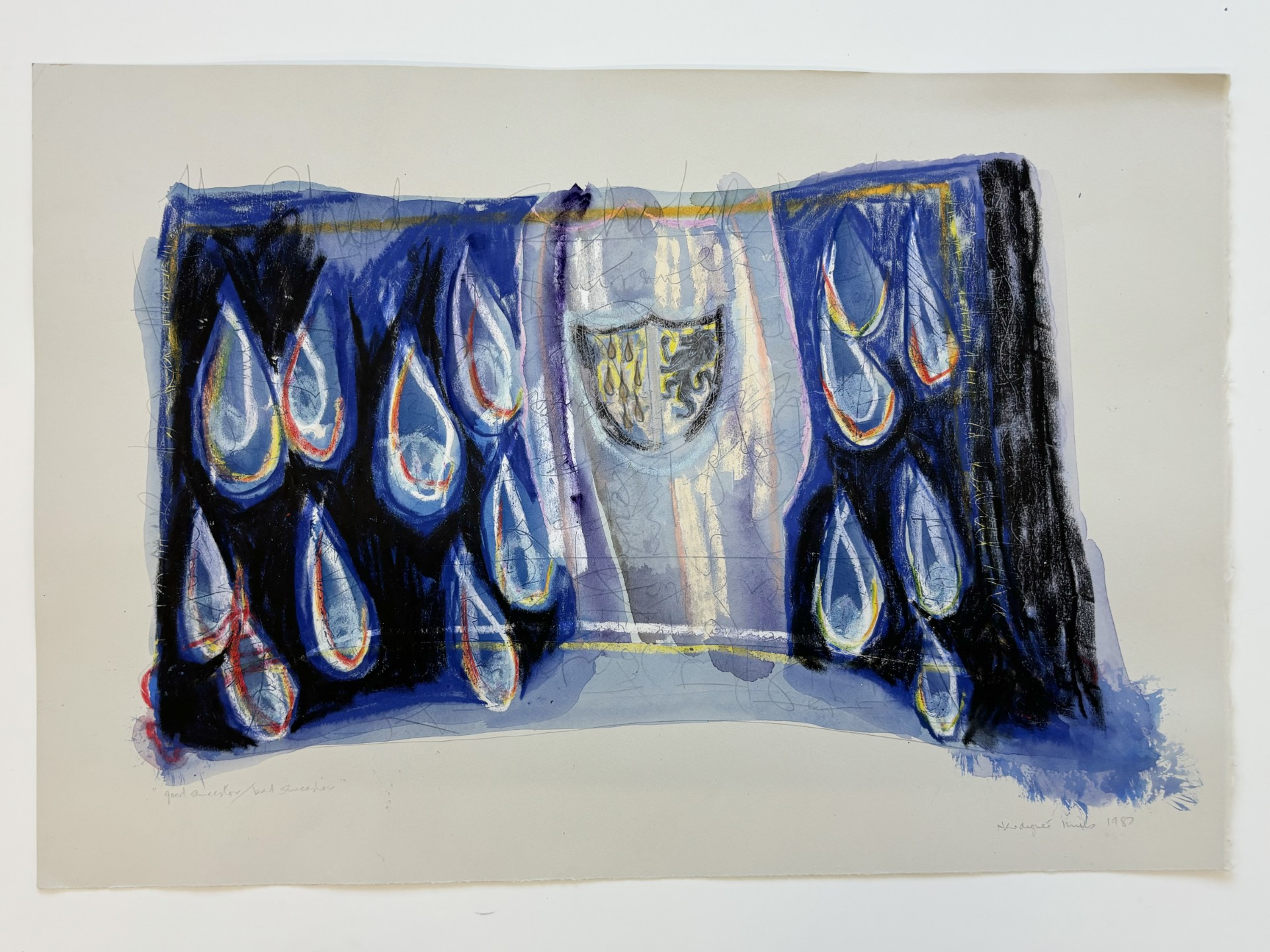

Feature Image: Ann Newdigate, Good Ancestor/Bad Ancestor, watercolour, pen & mixed media on paper, 1987, 38 x 56 cm. Family of Ann Newdigate, AGGV2025.001.005. Photo credit: Alice MacKenzie, Grenville + Fille