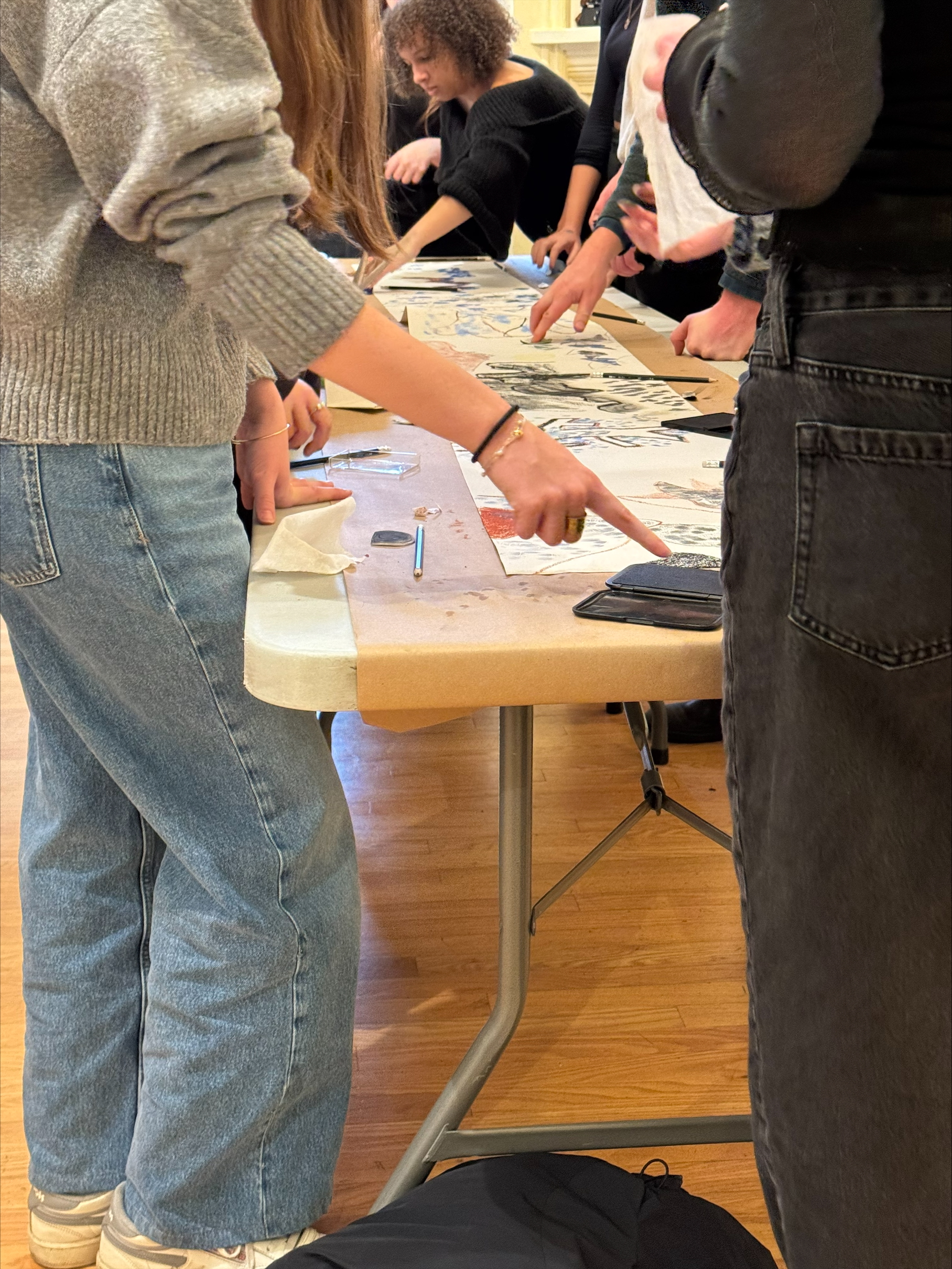

Soon after settling into his new role in Victoria, Colin Graham oversaw the opening of exhibitions in the Spencer mansion and the launch of art classes, along with film screenings, tours, musical and theatrical performances, and lectures. Activity at 1040 Moss was constant – and Graham wanted it this way. Graham’s purpose was to create such a “beehive of activity” that the organization could not fail because too many cultural communities would have a stake in its prosperity and wellbeing. Numerous and varied classes for children and adults fulfilled Graham’s vision that the Centre be as much a studio space as it was an exhibition space:

“We are moving out of the phase when art galleries were considered the preserve of the privileged few into one where everyone in the city feels it is there for his or her pleasure (…) art is a recreation which is also therapeutic.” The multifaceted approach to programming quickly gained a reputation. In 1954 local arts critic Audrey Johnson visited the Centre on a dark rainy February morning and described a lively scene: “as soon as I stepped inside the doors of 1040 Moss Street my tensions were eased by a sensation of harmony. It is a feeling that comes from the spacious rooms, the quiet background tones, the smiling welcome of those in charge, an atmosphere of accomplishment and cooperation. Underlying this was a quiet hum of activity; not the feverish activity most people experience continually in their day-to-day lives, but the steady, purposeful contented activity of people busy with creative pursuits (…) From Curator Colin Graham to all the men and women who voluntarily assist with the manifold activities, there is an impression of selfless dedication to a deeply held belief. It is one of the genuinely tolerant places, where cliques and snobbism are dissolved in the wine of shared experience; where all nations, all ages and all creeds are one. And this is probably the most essential and truest service of any to be found at the Centre. For it is the reason and the only valid one for the existence of culture (…) No great artists may ever eventuate from the children’s classes, it is true, but it is equally certain that good citizens will. Is that worthwhile I wonder to the taxpayers of the city and municipalities? That there should be any doubt in the minds of civic authorities is sufficient proof of the past need for just such influences as the Greater Victoria Arts Centre provides.”

Mark Kearley and the founding members of the Arts Centre would surely have felt both proud and vindicated after reading these words given the great effort made to secure a space where the activities Johnson described could flourish (and renowned artist Michael Morris would have taken exception to her suggestion no great artists would emerge – Morris was one of many successful artists who took these early lessons).

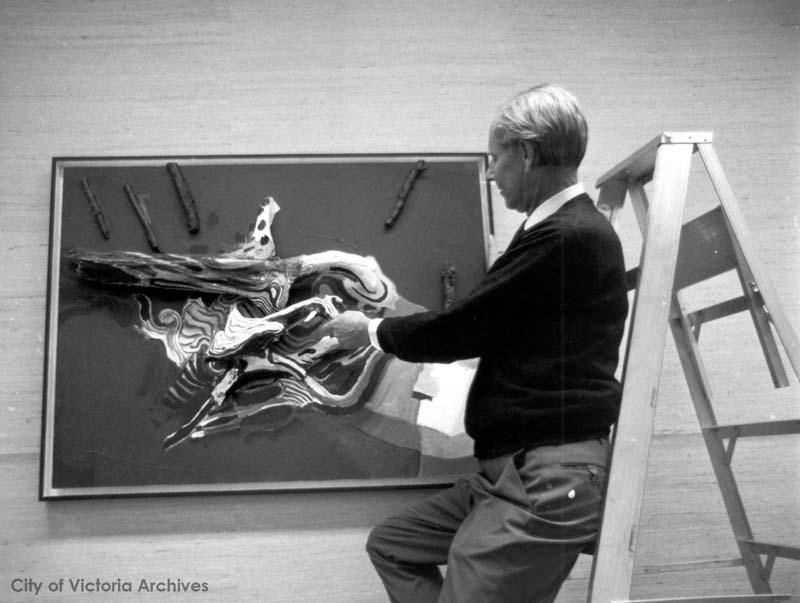

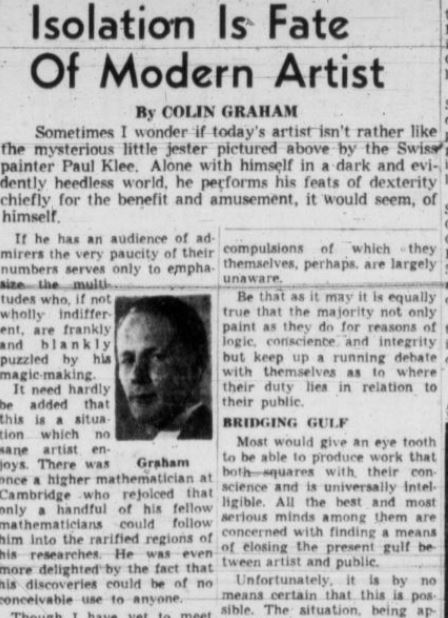

At a time when travel off the island was far less common, Graham felt that regular exhibitions (54 exhibitions were held in 1957 alone) were a way to expose the public to art they would otherwise not see (even if in some cases the works exhibited were duplicates of original masterworks, as with a popular 1954 exhibit of Leonardo Da Vinci reproductions. Not only was fine art on display, but also theatrical, architectural, and industrial design. Graham was an educator by training and profession before taking on his role as a gallery Director/Curator and he felt a responsibility to ensure those who visited the Arts Centre had a wide visual vocabulary. In 1954 he began writing a regular column in the Victoria Daily Times under the title “Special Reviewer.” As he later said, “this somewhat backdoor way of getting reviews of the gallery’s shows was necessary if we were to build up any kind of informed audience.”

These articles introduced the reader to trends and art movements – from American modern painting to the European avant-garde – but also delved into art techniques and terminology. He wrote in depth about children’s art and the societal need to not just support but exalt children’s imaginations and their exposure to a range of artistic experimentation. Able and cooperative by nature, Graham’s approach was inviting – height of brow was no impediment to accessing the Centre and its programming (before additional curators were hired, he scheduled regular juried shows so that it was not only his taste on display). Art education was inarguably at the core of the Centre’s mandate and of Graham’s frequent lectures and newspaper articles, but he had reservations about the lugubrious phrase, saying in 1955 that it conjured up “images of self-important educators dispensing their wares to the enlightened with a barely concealed holier than thou attitude.”

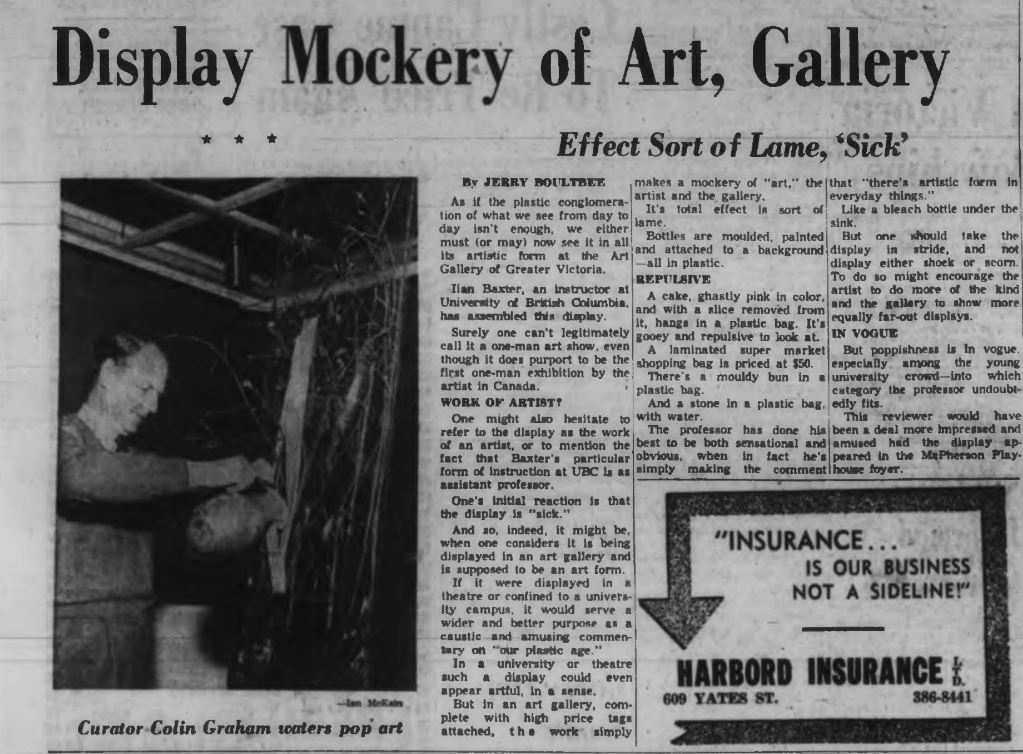

Graham championed wit, pleasure, and enthusiasm when Centre staff and volunteers engaged the public in conversations about art – “schoolmarm pretension” was actively discouraged. His messaging in the media and in the community was always to emphasize the only ask of the visitor was that they be curious – and even that trait could be sparked by a skilled educator or exhibition animater. He deftly responded to occasional visitor alarm over nudity or art deemed in bad taste. He invited conversation and took up the oft-challenging task of assuaging the anxieties of those patrons who, even in the 1950s and 1960s, were holding firm to the Edwardian era. When pop and “plastic” arts emerged in the 196Os Graham was as receptive as he had been with the abstract art that had provoked audiences in the 1950s. A 1966 review in the Daily Colonist called an exhibit by conceptual artist Iain Baxter (founder of the N.E. Thing Co.) “sick,” “repulsive,” and “a mockery of art, the artist, and the gallery.” The photograph accompanying the article perfectly captured Graham’s dedication to his gallery and the community of artists it served: an image of Graham dutifully watering Baxter’s stone in a plastic bag. As he once said, “art is a serious business, but surely not a solemn one.”

– Written by Anu Henderson, AGGV Administrator, Curatorial and Learning & Engagement.

Enjoy previous editions of the series, How the AGGV Began: