By Audrey Wang, AGGV Volunteer

The realm of mythical beasts spans every culture and exists in all our folklore. We not only find them in our intangible heritage, but also in contemporary literature, art, film, science and culture. In the AGGV’s extensive collection of European, North American, First Nations and Asian art, a menagerie of fantastic beasts reveal countless stories.

In medieval tales from Europe, the dragon was the fearsome creature to be slain by the heroic knight. Quite the opposite in China where the dragon was revered as the symbol of the emperor. The image of the Chinese dragon stands for power, benevolence and good luck. In dynastic China, the five-clawed imperial dragon can be found on nearly everything from the palace, including architecture, furniture, porcelain, artworks, garments and jewellery.

In the embroidered panel above, the imperial dragon is represented with gold scales, striding with great vitality over a turbulent sea in pursuit of a flaming pearl. The composition is repeated as a row of medallions above. This is a typical depiction of the Chinese dragon chasing the pearl of wisdom and surrounded by a variety of auspicious symbols.

The Japanese Buddhist lion in the featured image above derives from the Chinese version which is often found in sculpture form as a pair of sentry guards at the entrance to temples, palaces or tombs. One of the lions is usually female and is sometimes represented with cubs. This smaller incenser burner depicts one such cub playing with a “brocade” ball.

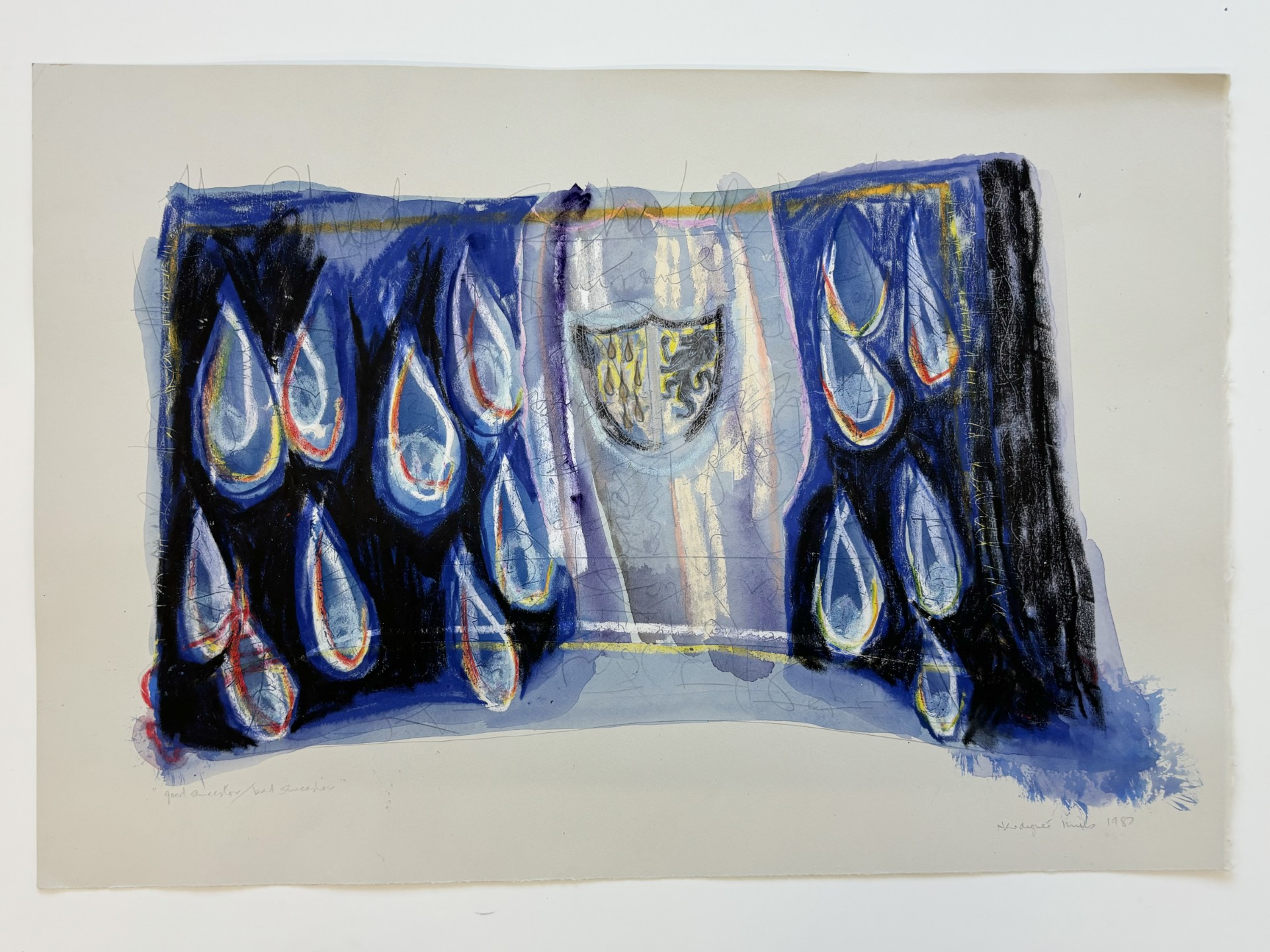

The butterfly is a dominant theme in Jack Shadbolt’s oeuvre, as a transformation motif. The AGGV has three such paintings with the artist’s signature featuring prominently with each central butterfly, each work having been painted over a poster from his exhibition of “Butterfly Transformations” at the AGGV in 1988. Shadbolt’s butterflies are not the delicate little insects one usually associates with the species, but are large, solid beasts, distinctly patterned and powerfully present. Shadbolt worked on this theme through the 1970s and 80s, creating marvellously varied versions of the same subject-matter, but each exuding a distinctive emotion, some joyous, others ominous.

Charles Elliott has lived all his life on Vancouver Island as a member of the T’sartlip First Nation. As a master carver and a pioneer in the revival of Salish art, he creates both three-dimensional and two-dimensional works that reflect the history and the concerns of his people. The seal is a salient theme in Coast Salish art as it represents abundance.

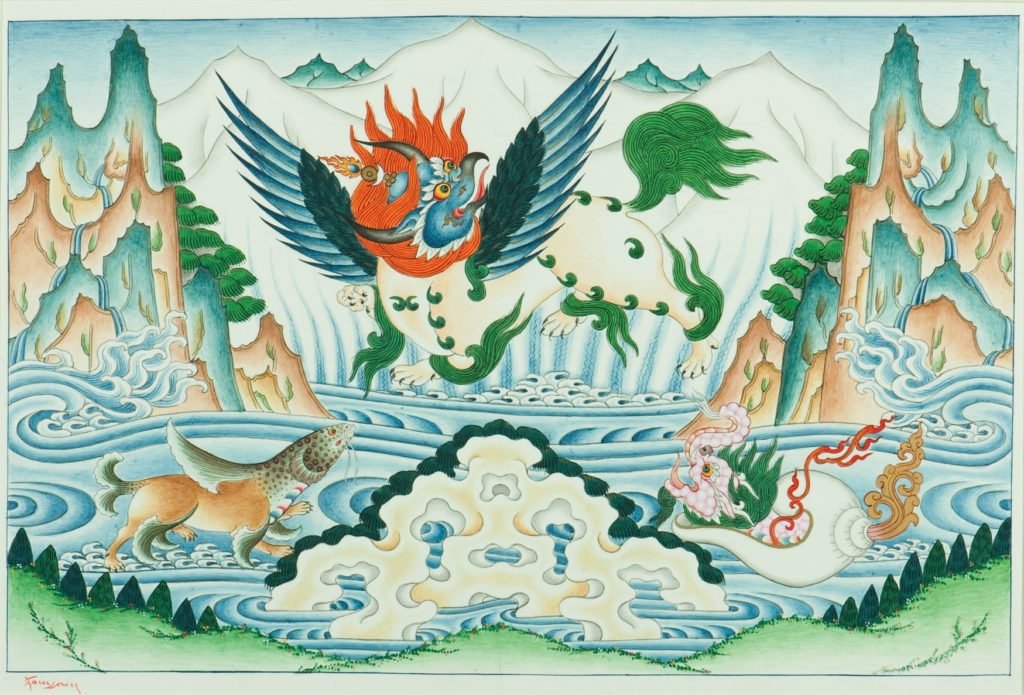

The Pairing of Opposites by Tsering Topgyal offers a radical departure from the rigid iconography of Tibetan art. In the artist’s comments, au verso, he writes: “Harmony is achieved by putting traditional foes together the head of a fish on a mink, crocodile and conch shell, snow lion and Garuda bird.” This theme of union, whether of colour combinations or male-female polarities, runs throughout trans-Himalayan tantric art. Topgyal here has stepped beyond the coded formalities of the past and updated the polarities concept to today.

Featured above: A stoneware Buddhist lion incense burner | Japanese, 19th century | Fred & Isabel Pollard Collection