By Audrey Wang, AGGV Volunteer

Gathered in the Tender Works exhibition gallery in a large circle were the artists – Tiffany Joseph, Farheen HaQ, Kerri Flannigan and Chase Joynt – their friends and other visitors, several of whom came as family units. The family, as well as one’s lineage, was a pertinent theme of the evening, even as the question posed to the artists related to the exhibition title: Where does the tenderness come from?

Artist Tiffany Joseph kicked off the event with an introduction of herself that included naming her parents and grandparents, a practice that served as a history and a passport when traveling amongst Indigenous communities. By acknowledging not only blood relations but also those who raised her, an idea of belonging is created, an important responsibility, especially when teaching about truth and reconciliation. So, everyone in the circle had a chance to take her lead and introduce themselves to their neighbours.

Tiffany’s video in the show is “MEQs LÁ,TEṈ ȽTE – Everything We Have Prepared”, the story of ȽÁU, WELṈEW Tribal School which was built to teach the SENCOTEN language as well as Coast Salish songs and culture. Tenderness, for Tiffany, comes from the connection with the ecosystem and the food source of her people. Landscape shapes identities and connectivities. With an understanding of the source, then comes acknowledgment of one’s lineage and birthrights. The School that Tiffany works at serves as an “Indian re-education”, bringing Indigenous language and culture back to its students.

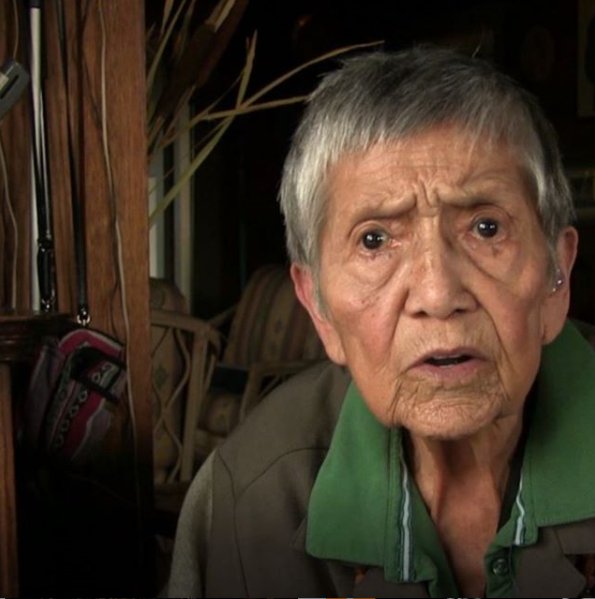

Farheen HaQ’s video work entitled “Drinking through my mother’s saucer” touches upon connections with her mother and their cultural background. Using the drinking of chai as the subject of the work, Farheen explains that much of her work is about what it means to be here as a guest on these territories, what it means to be her and what it means to be Muslim. It is a very human endeavour to ask “who am I?” and “where do I belong?”. For Farheen, motherhood became a profound experience in its allowing her to get in touch with humanness and tenderness, thereby shaping her identity. Her own experience of motherhood showed her the whole spectrum of emotions, and it prompted her to examine her relationship with her own mother. Coming from a patriarchal culture, there was little acknowledgment of her mother, and this realization brought her grief. The video comes from Farheen’s desire to honour her mother with the teacup representing the mother’s body.

Chase Joynt’s video “Akin” (2012) also examines the artist’s relationship with his mother as each entered a period of transitioning, Chase from female to male, and his mother from Christianity to Orthodox Judaism. In this project, the documenting of the transitioning process takes place through the archive of the past, as the two of them take a road trip to the neighbourhood where Chase grew up. He explained that the video was about the “unspeakability of place”, while also trying to make sense of the female body.

A final discussion at the event centered around the use of video as a format for story-telling. All agreed that the intimate and personal characteristic of film-making allowed dislocated migrants to find themselves, that it was a way to find common ground. AGGV Curator Nicole Stanbridge also gave an insight into the background of the show, choosing video as the medium because the viewer was forced to sit with it, donning headphones to cut out any peripheral distraction, and thus, be immersed in the world before them. Video is both interactive and intimate. The session ended with a question posed to all in attendance to think about as they wandered through the gallery: Who makes you feel cared for?

Feature image: Farheen HaQ | Drinking from my mother’s saucer | 2015 | video (still), duration 2:09 minutes | Courtesy of the Artist.